When it comes to the realisation of major urban interventions, São Paulo is lagging behind other world cities. Buenos Aires, our closest neighbour, has with Puerto Madero succeeded in creating a high-end development on brownfield industrial land, which attracts business and visitors, despite its lack of integration within the city.

Sites identified by the city authorities for urban regeneration, Operações Urbanas (urban interventions), include areas often – but not always – adjacent to existing transport infrastructure.

But who wins and who loses in these projects? How are these projects delivered? What institutional arrangements impact on design quality and the creation of sustainable environments? How many jobs are created? And for whom? These are the questions that São Paulo’s political, design and development communities need to address to formulate a new urban policy and to deliver a strategy to implement high quality urban design that works with the grain of the city.

Many of the international success stories in the regeneration of large-scale sites – such as redundant ports, railway, manufacturing and transport areas – suggest that considerable levels of public investment and management are necessary to make them work. In Brazil the private sector has historically taken the lead due to the lack of public funding or involvement in urban regeneration. Yet, a long-term perspective is a prerequisite of sustainable planning as opposed to the short-term returns on investment required by any commercial operator. In Washington DC, for example, the Corporation for the Development of Pennsylvania Avenue developed a 25-year vision for the regeneration of the area. The establishment of a delivery vehicle – an administrative structure with strong public as well as private sector representation – that manages and implements the project from inception to realisation is critical to its success in promoting economic development and generating new activities.

The compact city model, with its reduced energy footprint that promotes intensification of well-connected inner city sites, has become the central objective of many European cities. Urban containment, smart growth and sustainable development within a defined urban footprint are central components of this new urban vision that not only drives the identification of individual sites – often highly contaminated areas near the centre – but also shapes policies that promote sustainable living such as the introduction of the Congestion Charge in London or the Velib public bicycle in Paris. This approach has driven the development of a new urban hub at Paris Rive Gauche on the Eastern edge of the city – coordinated by SEMAPA (Société d'Economie Mixte de Paris) – which has attracted 60,000 jobs, counterbalancing Paris’s better-known financial centre at La Defense in the West.

Paris has developed its urban interventions within a clear regional and metropolitan perspective of economic restructuring that prioritises the international service sector, while London has focused some of its spatial policies on the creative industries through the actions of the Mayor’s London Development Agency. Bilbão, instead, developed plans at various regional and metropolitan scales before empowering the RIA2000 agency with the strategic implementation of the plan that gave rise to Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum, Norman Foster’s metro stations and Santiago Calatrava’s bridge. These interventions were instrumental elements of a successful marketing strategy that has promoted the city as tourist destination, placing it in competition with world capitals.

The wide-scale adoption of neo-liberal ideologies and their impacts on social exclusion has led to what Neil Smith has identified as the new ‘global strategy for gentrification’. In Paris traditional, old-style policies – enshrined in the ZAC (Zones d'Amenagement Concertés) – still constitute the legal starting point for urban and social housing projects, as they do across the whole of France. Exceptions to this rule are the implementation structures applied to the redevelopment of Paris Rive Gauche, Parc Citroën, Bercy and the former Renault car-works area. In the case of Paris Rive Gauche, a direct confrontation with the local community resulted in the provision of an appropriate number of affordable housing units and the incorporation of an old industrial mill as the seat of this industrial mobilisation.

The evidence from these projects points to the development of new management tools and the involvement of a wider range of social agents to better define successful urban regeneration. A key element is public transport, a critical component of sustainable urban development. Canary Wharf, the massive office and commercial complex in London’s East, only took off after the Jubilee Line extension connected it to the city’s main metro network. The success of the Kings Cross development and the London 2012 Olympics site in the Lower Lea Valley are also highly dependent on their location next to major rail-based transport hubs that will create higher density clusters of a polycentric nature. In Milan, the viable redevelopment of ex-industrial sites at La Bovisa and La Biccoca into major office and residential neighbourhoods were predicated on their proximity to the city’s extensive public transport network.

By analysing international case studies, it becomes clear that the state has played a key role in their implementation, despite the high level of private sector investment. Even in the United States there is evidence of substantial public investment – at federal, state and city level – to implement infrastructure, transport, public spaces and cultural institutions in major urban projects. Another lesson is that solutions to urban problems depend on the involvement of local actors, civil society and the active participation of government at many levels. On balance it can be observed that highly centralised traditional planning tools which regulate land use and urban development – as they are currently implemented in Brazil – have become obsolete.

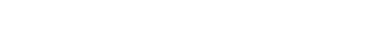

São Paulo’s strategic plan – the Plano Director Estrategico – is a case in point. The PDE 2000 determined that 20 per cent of its built-up area should become sites for Operações Urbana (urban interventions). To date these have been the subject of repeated criticism with piecemeal results which lack a comprehensive vision of urban design. There is no vision for a sustainable urban model with clear environmental objectives, nor has there been any public debate about public space and rebalancing the role of public transport and the private car in the city’s future.

The crisis of contemporary Brazilian urbanism reflects the weakness of the system of large-scale ‘strategic masterplans’, which wrongly assume that all urban problems can be solved by one single instrument. The successful strategy for city-level ‘urban interventions’ must be considered as an instrument of structural transformation, built on a partnership between the public and private sectors. It is a process that requires the participation of landowners, investors, residents and representatives of civil society which identifies particular urban areas for transformation as part of a wider metropolitan strategy. To be implemented successfully, such a strategy requires a series of medium and long-term measures, including land tenure reform, evaluation of real estate potential, strict land use regulations and public space interventions.

The São Paulo experience has since the 1990s failed to deliver an effective and democratic urban vision for the city. The major reason for this failure is the absence of a proper management and implementation vehicle that takes into account the full social and economic costs and benefits of projects of this scale and complexity. Any intervention of this sort must embrace the various actors and agents involved in the production of city space, constructing a communal fabric that values the individual citizen. Yet, this approach assumes public engagement to achieve a shared objective. Demolition of entire pieces of city and their replacement by ‘model’ projects will do little to improve the lives of existing urban dwellers, and will simply cause displacement and erosion of its existing social and urban fabric.

Given the extreme levels of social inequality found in most Brazilian cities we would argue that a more subtle and sophisticated approach to urban regeneration is necessary: one that is based on a collective effort and broad participation, and that aims to promote local development and social inclusion. To this end we would suggest that São Paulo adopts a new system for the implementation of its urban interventions founded on the following principles: require a clear political commitment to implementation, innovation and inclusion through a metropolitan masterplan that integrates the development potential of urban sites with public transport provision; establish a legal framework that promotes social inclusion and public participation (by creating a Participatory Management Forum for individual urban projects); establish an independent local development agency to implement specific urban projects, that includes all key stakeholders and is responsible for project management and delivery, inward investment, funding and project financing; develop an integrated mobility plan that optimises public transport use incorporating metro, bus, bicycle and pedestrian movements and minimises private car dependency; establish a metropolitan-wide development fund that can capture value of future return on investments; promote a sustainable environmental approach that integrates the remediation of water and river systems with redevelopment of brownfield land; propose mixed-use centres that provide housing and employment and support the ‘new economy’; and identify special conservation areas across the city that take into account the historic value and architectural merit of buildings and spaces.

note

1

Text by Urban Age – South America Conference, São Paulo, december 2008

about the authors

Nadia Somekh is the professor of the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at the Mackenzie Presbyterian University

Carlos Leite is an architect with a PhD in sustainable urban development and is a professor at Mackenzie Presbyterian University