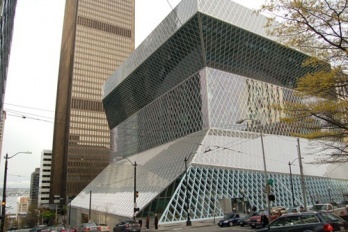

Biblioteca pública de Seattle, projeto de Rem Koolhaas, com o estuário Puget ao fundo

Foto Alessandro Filla Rosaneli, 2008

Anne Vernez Moudon: That’s what we are trying to do here in integrating urban design and planning. We don’t expect that every student will become an urban designer, but we try to get students from architecture, landscape architecture and urban planning, and to put them together in order for them to have a common knowledge for the city. This is a good way to start, with a lot of experiential sort of stuff, going out to experience the city, etc. But we also have to convince some students to take these urban design courses because they are not required. An architecture student is not required to take an urban planning course and vice-versa. This is strange because we are in the same College of Architecture and Urban Planning! In my past studies in an American University (UC Berkeley), I had to take a required urban planning course. This need to relate building design and construction to urban planning is in many ways why I’m teaching the urban form course as an architectural approach to urban planning. This type of approach is very important not only to appreciate “places” but to understand how cities are produced. Urban planning is often so divorced in scale from the development process. In this country, some years ago, planning Schools loved to admit lots of students, from just about any background except architecture! [rs] Urban planning at that time was trying to be against physical form, against physical determinism. Everything was socially and economically oriented. Planners were trying to make people believe that cities were only social or economic entities. Now things have changed. The reason we don’t have just Planning Schools is because the planning system is not that strong. Finally, I would say that planners and architects, when they acted as separate entities, developed their own sort of theories. As a result, I believe we are still lacking good theories in which work at an urban design scale. There is lots of work to be done in this area.

AFR / DSP: Your main topic research has been changed along the years, however, all relates significantly to urban environment and urban form. In addition, your researches mainly relay on quantitative methods, rather than qualitative, that measures different elements or aspects in the urban environment. When and how you have discovered that the fundamental base for research is to examine the objective and the quantitative elements first? What are your aspirations to your research topics? What was your inspiration towards your new research topic of Urban Environment and Health?

AVM: Considering the objective elements of space were done in the research about San Francisco. At the same time, that work was very architectural. I used an environment and behavior approach. So I’m always concerned with the objective questions of the environment and with the affordance of space: how do people use it, how can they use it, and so on. My research topics after the San Francisco work focused on the Boston and the Seattle metropolitan areas looking at infill strategies and new building types. I used to teach in a lot of studios on this topic. At that time, we were concerned with mixing buildings types and uses, a common topic now, but my architecture colleagues thought that I was crazy at the time… This was a great innovation, mixed-use buildings in contemporary settings! Can you believe this? But to the credit of Seattle, the zoning allowed mixed use in many areas! So I said to my colleagues: the zoning allows it and maybe we can show developers what they could do! At that time, I was waiting for GIS to come about. I edited the street book (Public Streets for Public Use, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1987). In parallel work, we found that for the same planning measures of density and mix of uses in neighborhoods, there were three time more people walking to the neighborhood commercial center in urban areas that had small blocks and sidewalks than in suburban areas with large blocks and few sidewalks. That was kind of cool! We also found that there were many more neighborhoods in suburban areas that had the potential for walking than anybody had thought existed. I got some research support to continue looking at the suburban neighborhood clusters. This is when we started doing work with walking and transportation. At his time, in the 90s, there was no concern about health. It was all about transportation. The health issues came in much later. Public Health people contacted the transportation people who were doing the research on walking. And these transportation people in turn contacted me. We all had meetings for years. We had great time thinking about how to increase opportunities for more walking cities. Yet we kept saying: Why are we meeting? Nobody is paying us to work, nobody is “feeding us”! The frustration was enormous. I finally received a grant to study the health and walking question in early 2000s. That was a big project and I got so scared when I got this grant because we had so much to learn!

AFR / DSP: Finally a few questions about your life and…

AVM: Oh, my life? It’s almost done! [rs] Let’s go to have a drink! [rs]