An urban settlement as an ecosystem

Illustration by Soham De and Prachi Rampuria, INSD

Paula Barros: Different metaphors for representing, describing and explaining the city have been created, such as: city as work of art, city as machine, city as organic entity and, more recently, city as ecosystem. Assuming that metaphors influence what urban designers pay attention to, which analogy, in your opinion, best describes the contemporary city and how it may inspire ways of designing it?

Ian Bentley: I don”t see these paradigms as necessarily conflicting with each other. Rather they are alternative, overlapping perspectives on human settlements. From each perspective, particular factors stand out clearly, whilst others are hidden.

Since each of them has its army of convinced adherents, it is really rather unlikely that any of them is “wrong” in any absolute sense. Rather, I see them all as “partial truths”, each worthy of critical respect. What is wrong is to think (or even worse to feel) that any of them represents the whole truth; and that what stands out from any particular perspective – what counts as data – is therefore all that matters. Because these are only partial truths (we have to remember that any model has to be simpler than the system it describes/explains if it is to be of any practical use), and the forces affecting any settlement necessarily vary over time, any metaphor that we employ has constantly to be reinterpreted, if it is to stay useful over time.

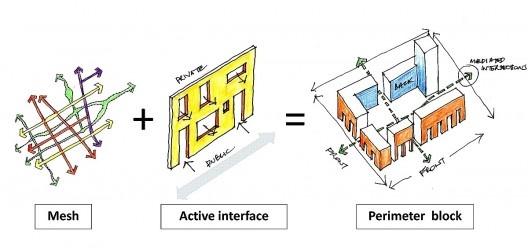

Often, this reinterpretation doesn”t happen often enough; particularly when certain interpretations are appropriated as ideological supports for maintaining some political-economic status quo. An example of what I mean here might be “city as art work”, which has been taken over to justify the production of commodified “iconic buildings”. It might be more progressive to ask “what kind of art is relevant for a designer trying to produce a responsive place?” A “progressive” answer might be “performance art”, where the designer is creatively performing a particular repertoire of responsive “keystone principles” – active interfaces, mixed use areas, highly-connected street networks and so forth – an approach to the arts of architecture or urban design that is more like dance or music than painting, for example.

I am not personally a relativist, however: I certainly don”t think that each of these paradigms is equally useful to designers at the present juncture. I find that the understanding of “settlement as ecosystem” has moved ever nearer the centre of my own thinking, for two main reasons. First, it helps us break down the artificial mental barrier between “humans” and “nature” that is built deeply (and destructively) into so many “western” cultures. Second, it reminds us to take as holistic an approach to design as we can.

PB: Could you say more about your understanding of “settlement as ecosystem”?

IB: A key characteristic of any ecosystem is that it consists of “systems within systems”, as Janine Benyus puts it. Each of these systems is a “holon” – a whole that is in turn part of a larger whole, and contains smaller ones within it. Each of these constituent systems has to be viable (however defined) in itself, whilst the relationships between the systems are crucial to the viability of the larger whole. The whole concept is essentially a dynamic one.

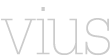

This seems a very helpful way of thinking about a city. Cities are made up from a set of different systems – landform, water system, green system, public linkage network, plots, buildings and components – which are differentiated not only spatially, but also because they change at different rates through time. The underlying landform, for example, lasts through geological time. Aspects of the public linkage system typically last through millennia. Plots might last for hundreds of years, whilst buildings are often redeveloped after only a few decades.

This understanding of how time is embedded in urban structures, and the sensibility that follows from it, seem essential for addressing the issues of sustainability (which is essentially about time) which challenge us today. At a conceptual level, I also find it an aesthetically stimulating way of thinking about urban form – it excites me!

Spatial knowledge evolving through time

Illustration by the interviewee

PB: What is the value of urban design today?

IB: Urban design (which is itself due for reinterpretation, so I tend increasingly to refer to a “broadened” version that I call “settlement design”), helps us to understand that the individual elements that make up human settlements – buildings, infrastructure, parks, streams and so forth – are all components in the construction of a larger settlement system. It is this larger system that we experience in our everyday lives; and we can”t optimise it by trying myopically to optimise each individual element. Urban design helps us remember this.

PB: While urban design is founded on the premise that conscious actions may contribute for the betterment of cities, too often urban settlements designed as a single finite object have not been perceived as spaces responsive to human needs. To what extent should urban settlements be designed?

IB: All settlements are inevitably designed, even if through some “bottom-up” process, because they are the result of an aggregation of human decisions – and remember that the decisions are always aggregated, even in the most centralised, top-down process. No city has ever been designed as a single finite object; though many designers have tried to make that happen. The question is really about how the aggregation should be organised, I think.

Historically, design innovation was limited by constraints on materials, finance and knowledge which have now been loosened in developed and developing economies. In the earlier situation, there was plenty of small-scale innovation, but settlements developed relatively slowly, so there was time to evaluate whether any particular innovation was successful or not, measured against the values of the time and place. Innovations that failed were too small to have a catastrophic impact on any settlement as a whole. Innovations that turned out to have positive impacts were replicated, whilst negative ones were not – and there was time to see the difference. “Traditional” ways of doing things therefore embodied a great deal of tacit, widely shared information about how to make good settlements.

Given expanding populations and growing rates of urbanisation, particularly in fast-developing economies, we cannot expect to go back to “slow innovation”. What we can do is discover how to recognise and use the spatial knowledge that has evolved – and continues to evolve – through practice, and is embodied in the tacit keystone principles that underlie today”s well-loved places. We have to articulate this knowledge so that designers can use it consciously in their work.

The idea is not to develop models to be copied, but rather to articulate keystone spatial principles to be used creatively. Indeed, the (very traditional) value of “originality” remains important for ensuring that the principles are constantly used in new and exploratory ways – the cultural equivalent of “disturbance” in ecology; ensuring that settlements held together by these keystones are still open to evolution.