A sculpture representing the Indian Deity Brahma

Photo by Soham De

Paula Barros: Carmona and his colleagues distinguish between “knowing” and “unknowing urban designers” (14). The former group would include those professionals employed for their urban design expertise as well as those people, such as developers, who acknowledge their own role in shaping urban landscapes, but do not consider themselves urban designers. The unknowing urban designers, by contrast, would be those people who make urban design decisions without appreciating that this is what they are doing, such as some politicians and providers of infra-structure. Which strategies should be used to enable knowing and unknowing urban designers to work cooperatively?

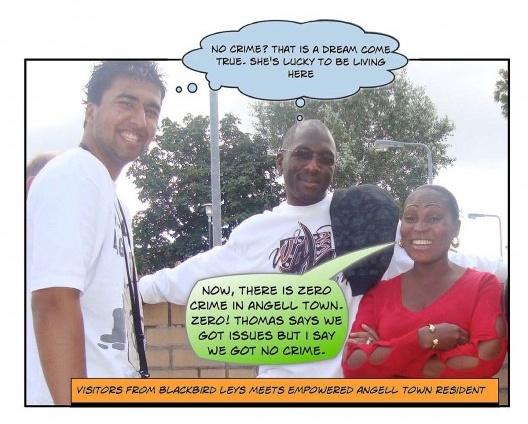

Ian Bentley: Direct participatory working between professionals and users, in the face-to-face sense, can be very valuable. I spent twenty-five years as an urban design activist working with concerned local residents of the Angell Town social housing district in South London, and many of the outcomes were very positive – the residents love the results, which have also won many design awards. However, this was an extremely resource-intensive process which, from my own perspective, would certainly not be possible with today”s UK university funding regimes. I no longer see it as a sustainable process that can be widely used in many places today.

As Angell Town taught me, a great deal of settlement design revolves around actors who have markedly different political, economic, social, ecological and other objectives. This means that there will always be conflict in the settlement design process. This will never go away, but perhaps it can be transformed from a war to a debate in good faith; in part through the development of a common language, capable of connecting with the factors that matter to all the different producers, consumers and controllers involved in the settlement process. This was one of our aims in RE, and to some extent it has worked – I”m always delighted when people say (as they sometimes do) that RE is “just common sense”, even though this is sometimes meant in a negative way. At Angell Town, we used RE as a “starter language”, and developed its vocabulary to connect with the residents” concerns. For example, we became very interested in the relationships between spatial structure and crime/security issues, which are completely missing from the original RE but are very important in the book we are working on now.

Residents at Angel Town were highly concerned with crime/security issues

Illustration by Regina Lim

PB: Accepting that urban settlements necessarily result from a conjoint effort, what specific concerns should planners, urban designers, landscape architects and architects bear in mind whenever the overall aim is to generate well-loved and well-used urban settlements?

IB: I think the specific concerns of practitioners depend on the way their specific practices have evolved, historically, in any particular place – it is certainly not just a matter of how their practice is “named”. For example, calling an academic course “Architecture and Urbanism” doesn”t necessarily mean that the people who graduate from it, and therefore have the right to call themselves “urbanists”, would necessarily understand urban systems in the same way as someone trained as an urban designer in a different educational system – the design professions have developed in significantly different ways in different places, through processes of evolution within different political economies facing different practical challenges at different historical periods.

Similar “names” therefore often mask very different practices. In Holland, for example, landscape architecture firms like West Eight usually have by far the widest and most holistic understanding of the context of settlement design; seeing architecture as concerned with the design of the small urban elements we call buildings. If I had my time over again, I personally think I would have been able to make more impact on settlement design if I had studied landscape design rather than architecture.

In the end, though, each local tradition has to do the best it can with whatever it can create from the professional structures it has inherited. I think there are two key concerns here.

First, we need a common language of concepts that can bridge across the inevitable differences of professional culture, both within and between specific places. RE has proved reasonably effective in this regard, but there is plenty of need for improvement. We hope that EcoRE will do better, because it pays specific attention to the particular subsystems – blue and green structures, the streets and infrastructure of the public linkage system, plots, buildings and components – with which the members of particular professions are concerned. We hope this new structure will help to remind everyone about how “their” concern fits into the larger picture.

Second, we all have to learn to operate with a kind of “double vision”. As well as looking “inwards” at the system that “belongs” to our own particular profession, we have to look outwards, to consider how it meshes with the other systems that make up the settlement as a larger whole. What matters far more than what we call ourselves, is the degree to which we can use our particular local professional traditions – whatever their particular strengths and weaknesses may be – in open, outgoing and flexible ways: I think that a really good “self image” for all of us involved in designing settlements is offered by the Indian deity Brahma, who manages to look in four directions at once, whilst still maintaining her inner sense of calm!

note

14

CARMONA, Matthew et al. Public places urban spaces: the dimensions of urban design. 2. ed. Amsterdam: Architectural Press, 2010, p. 4.