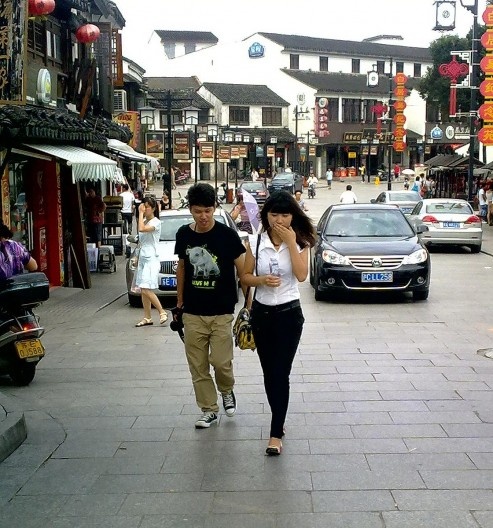

A view from the street in Suzhou, a traditional Chinese city

Photo by Prachi Rampuria

Paula Barros: Lynch argues that the aesthetic quality of urban settlements may be improved through education: “visual education impelling the citizen to act upon his visual world, and his action causing him to see more acutely” (16). Although the importance of designing urban spaces likely to offer a variety of enjoyable visual and non-visual sensory experiences was highlighted in RE, most of theory, practice and teaching of urban design have focused on the visual quality of urban open spaces. What educational strategies may propel known and unknown urban designers to pay more attention to the multisensory character of aesthetic experience throughout the collaborative process of designing urban settlements supportive of effective human functioning and, therefore, well-loved and well-used?

Ian Bentley: Sadly, I think that you are right that it is mostly UD that has tried to get designers to pay attention to the necessarily multisensory character of urban aesthetic experience. I say “sadly” because UD (in the UK at any rate) is only studied specifically at a post-graduate level; so students have already been brainwashed for years into ignoring all but the visual dimension of design (as I was myself). It is terribly difficult to break free from this kind of conditioning, even though computer technology now offers a certain potential for moving beyond traditional graphic expression into sound and movement fields. I don”t think we shall make much progress in this (hugely important) area until students in all the design fields, as well as kids in their school “art and design” lessons, are taught to pay attention to all the senses in their work.

Children enjoying a delightful multisensory experience

Photo by Gertje Kreuziger

PB: What do you think is the way forward to teach urban design in the globalized world of the new millennium?

IB: I”m not sure about “the” way forward, but I certainly think there is an interesting way of starting to address one of the many challenges of teaching urban design in a context of globalisation. One of the most difficult of these challenges, for teachers and students alike, is the increasing importance of what is sometimes called “glocalisation” – the intense, world-wide desire for places with some sense of local rootedness – and a consequent suspicion on the part of students that “universal” UD principles can never be valid in particular, local cultural contexts.

In my opinion, however, evidence from cities across the world shows that this suspicion is quite unwarranted. If I visit the traditional areas of a Chinese city like Suzhou, for example, it is certain that I shall understand none of the written street-signs that abound there. However, I shall instantly recognise that the city is made up from streets, water systems, plots, buildings and so forth – I can recognise these directly from my own European experience.

If I look more deeply, I can also see that most of the streets are linked into a highly-connected network, whilst different land-uses are related together to form mixed-use neighbourhoods – both “keystone principles” that I would advocate today. These same principles – and many others – seem to have evolved, independently, in many places with little past cultural contact – as “default settings” of traditional settlements across the globe; at least when the settlements concerned are of a scale that we would normally call a city. What fascinates me, however, is the fact that these “keystone” characteristics of spatial structure are given very different explanations in the contexts of different cultures.

For example, RE advocates highly-connected street systems because we claim that these increase permeability. The Chinese Feng Shui tradition, in contrast, sees streets as conduits for flows of energy – chi – and argues against culs de sac because these will obstruct the free flow of energy; which will then “stagnate” into “bad energy” – sha chi.

To take another example, RE advocates a variety of land-uses in an area because this offers more choice, will make the place more lively, and will increase the potential for security because there will be people around throughout the day and during the weekend. Feng Shui has an alternative justification. It sees different land-uses as having different proportions of male and female energy – yin and yang – and argues that any area without a mix of uses will be unbalanced in terms of these energies, which will lead to a lack of harmony in everyday life there.

This phenomenon – the independent emergence of the same set of spatial keystone principles, supported by very different cultural explanations – seems common across the world. It is currently attracting an increasing amount of research investigation; ranging from studies of India”s Vastu Shastra tradition to the anthropological invariance of time travel budgets.

UD education can use these “invariant” principles to connect with students from many different parts of the world. Of course, it is vital that the students (and teachers!) understand that these are spatial principles. They are not rigid models to be copied, but have to be differently interpreted by designers working in different localities. This is where the creative involvement of people from the local culture(s) is so important.

note

16

LYNCH, Kevin. The image of the city. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1960, p.120.