The photograph of Şeyda Sever is inseparable from her background and her political convictions.

Steeped in a small body, full of generosity, although marked by perseverance and self-confidence and a clearly demanding and asserting position, Şeyda Sever graduated as a journalist in 1991 but never worked as a full-time journalist. She works in a Swiss NGO for prevention and civic awareness on natural disasters (which in her case is focused on earthquakes).

Difficult to name her a ‘feminist’ as she is not an open activist. Her speech is founded clearly in favor of tolerance between religions, nations and genders and, in her way, she fights against gender inequities, and proposes a new interpretation, always the less obvious, about her country, Turkey. The famous essence of Turkey as a bridge between different worlds, goes beyond the geo-political issues and becomes one of the main themes in Seyda’s photograph. This bridge now reaffirms the recognition of individuality and personal relationships established in her travels around the world.

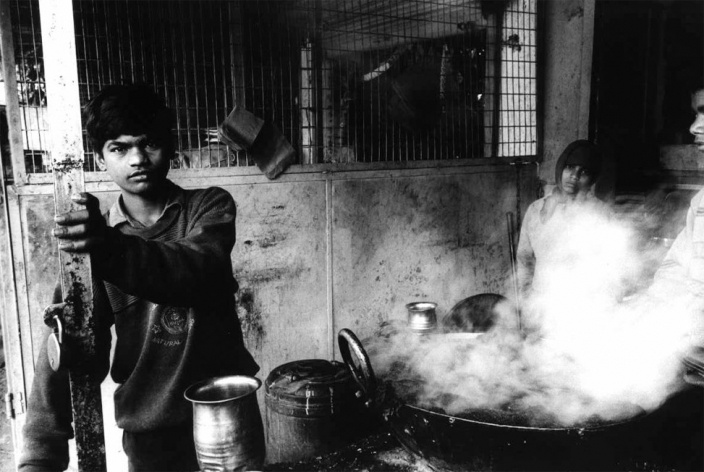

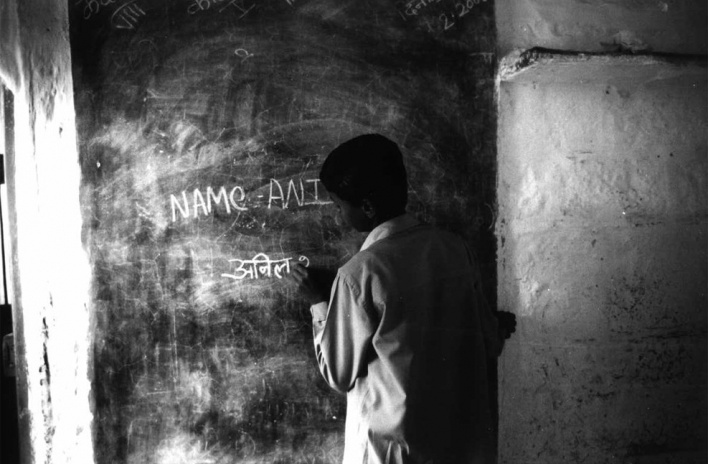

She doesn’t consider herself as s ‘photographer’, but despite her excessive modesty, she is able to transmit her personal struggle and the challenges brought by the dichotomy between the importance of recongnizing the value of individuality and the sense of 'belonging' of collectivity. Her world can be considered as a laboratory of religious tolerance, politics, inclusive nationalism and restlessness with injustice.

Şeyda was born in Rize, northeast Turkey, in a family of the “Laz” minority, on the shores of the Black Sea. The Laz language which has only 100,000 speakers is, according to Unesco, one of the languages in danger of extinction, and is threatened especially for the fact that it is not written. I believe that this condition of transition and threat, her fragile ethnic and linguistic minority, gave Şeyda the background for her curiosity, introspection and identity that she brings through her photography.

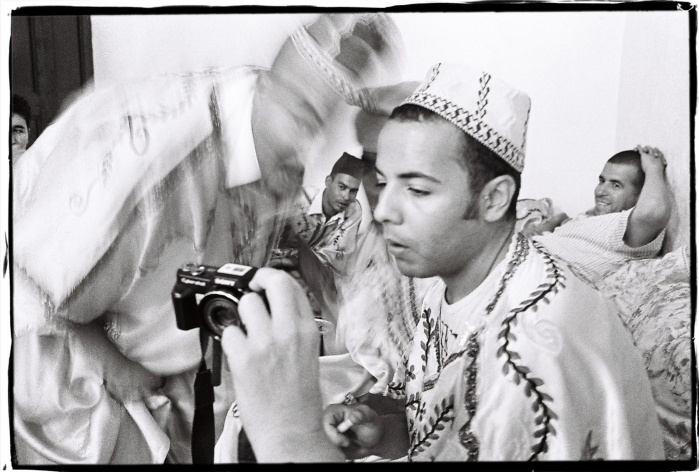

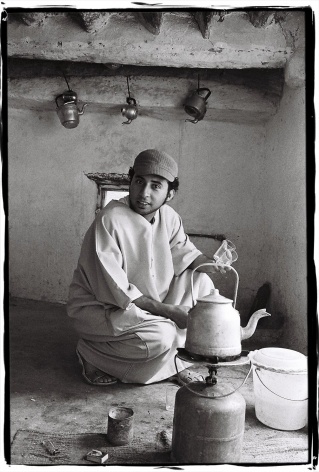

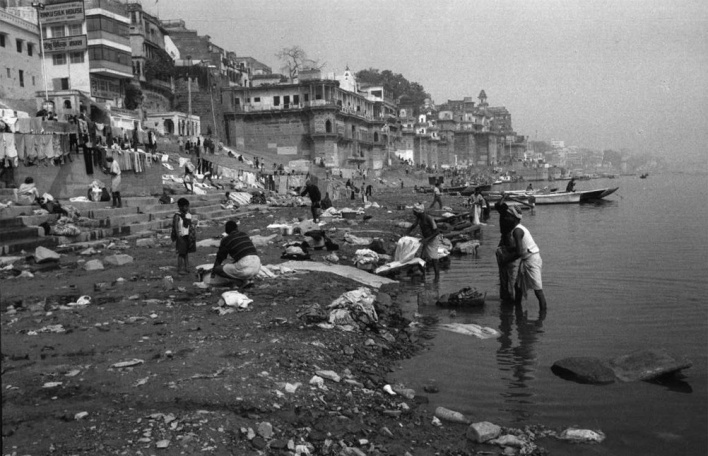

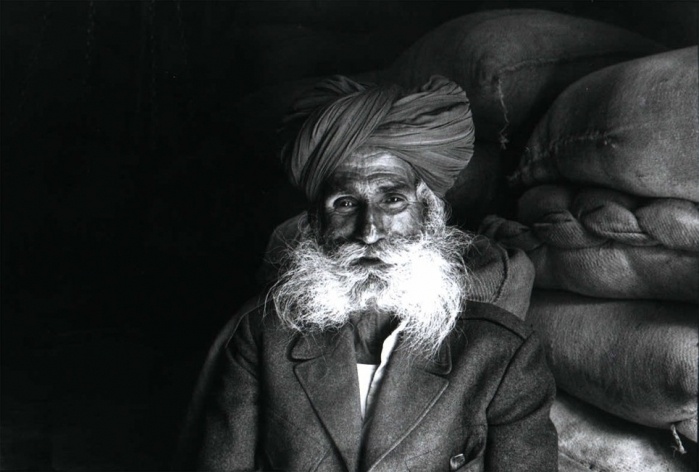

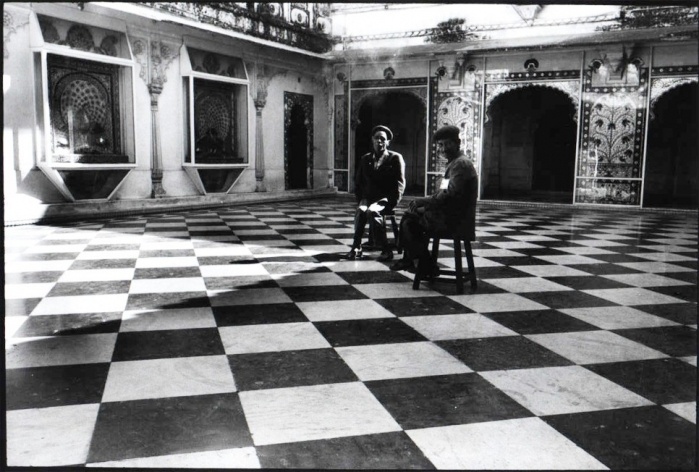

The spontaneity of her act of shooting converts the camera into a witness that overpasses the simple "representation" of the moment. The click is not "professional" and neither can be compared to photojournalist. If many of the technical and artistic characteristics match those of the great masters, somehow due to the same cameras used (a Leica M6 and Contax G2), the photography of Şeyda is inspiring because it contains the amount of tourist clichés and social tragedy present in photojournalism but at the same time glides over imperfection and an incredible domesticity.

Şeyda seems to be able to camouflage herself and become invisible behind her camera. The triad object/ medium/ subject ends up with an unusual balance here. The supremacy historically bequeathed to the object, merges with the background brought by the subject (without the naivity of the amateur, nor the wickedness of the professional), and also with the interest for the vicissitudes of the environment.

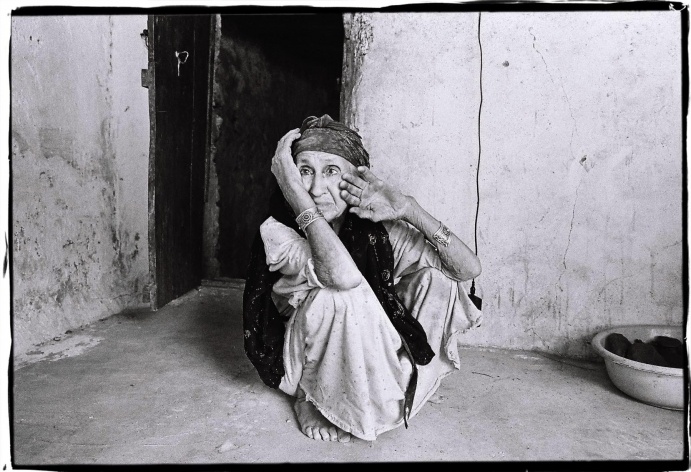

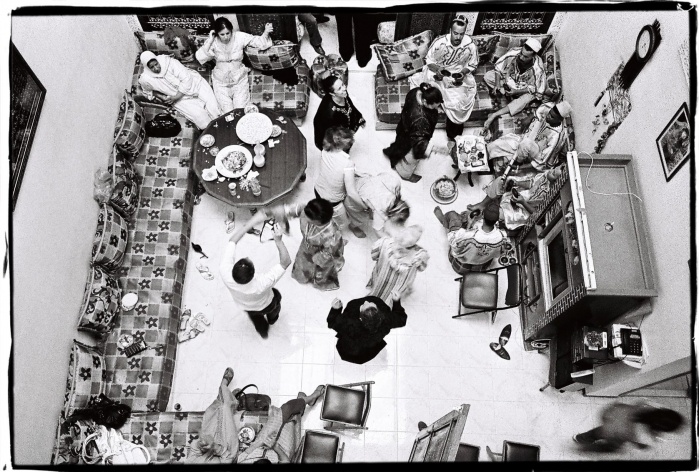

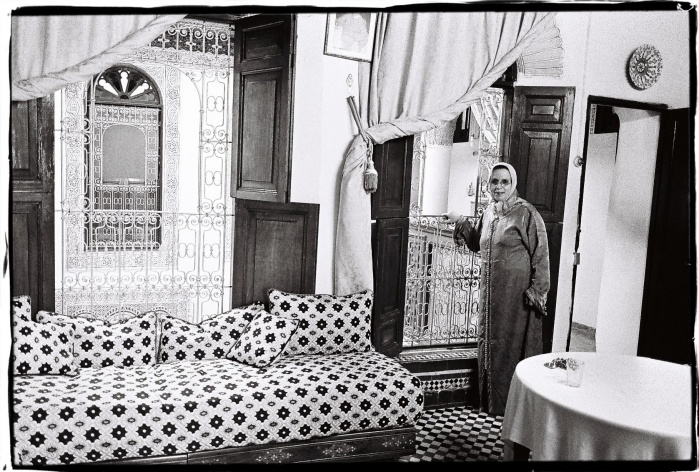

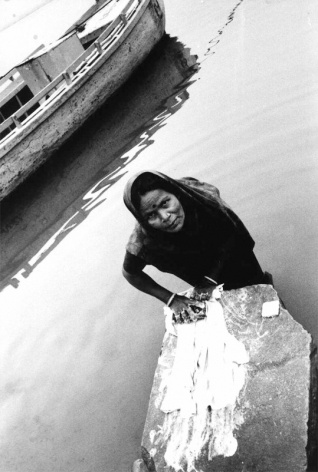

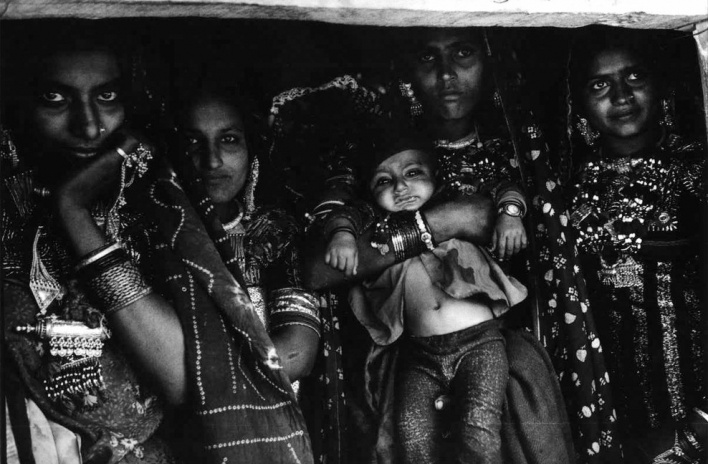

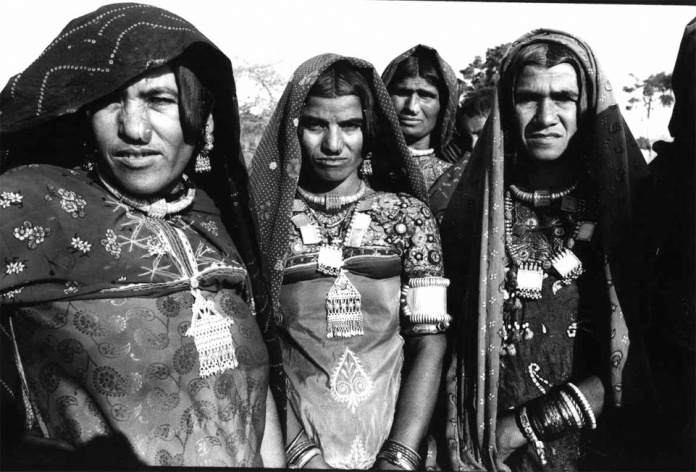

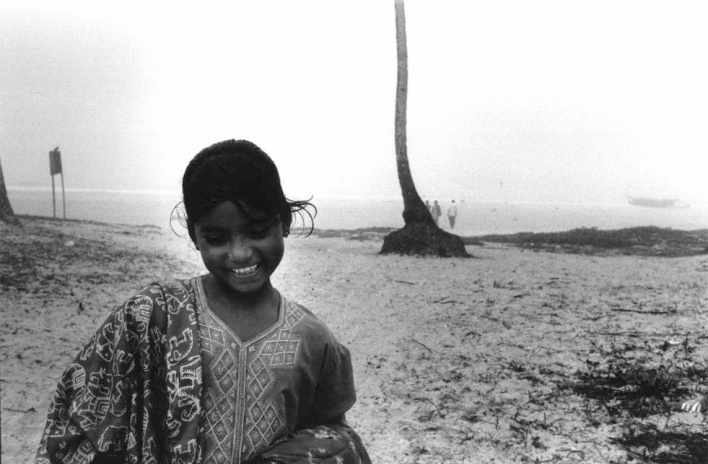

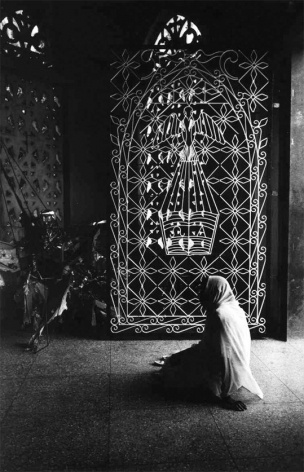

These characteristics make her a unique portrait photographer. I refer to the striking portrait of that lady squatting in Morocco, but also to the dramatic picture of the youngsters gathered in a circle of music in India, where we can’t ignore the fact that a woman was capable of portraying such a moment of relaxation in a sexist and patriarchal society. The pose, ie the preparation of the pictured, a few moments prior to the click, is very ephemeral in Seyda’s portraits, and only possible because of the instant complicity between subject and object. She crosses several times the boundary between photojournalism and a random and casual shoot. Her eye is able to identify crucial moments, and there is a confusing apparent lack of concern with the "composition".

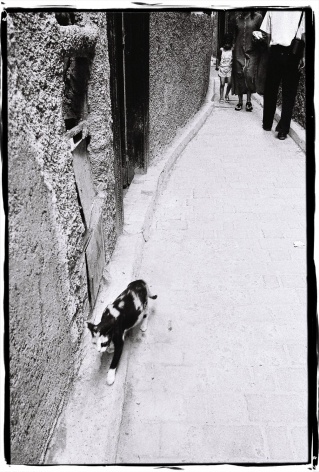

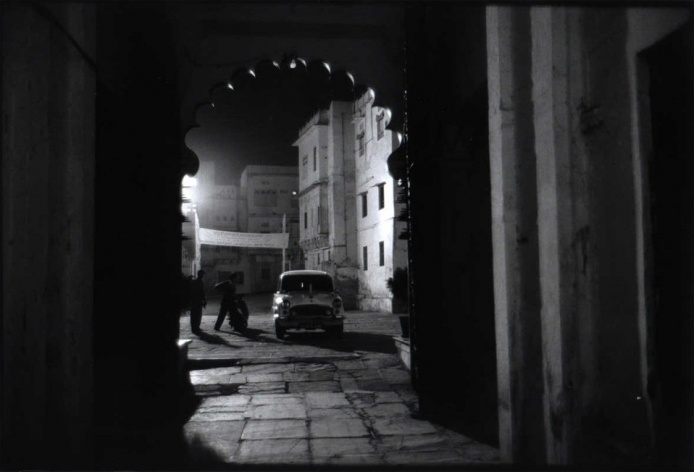

As an example let’s take the photo of that cat in Morocco, where the diagonal marks a dynamic line between the figure of the cat and the half-bodies at the background. We are unable to imagine the following moment after the click. “Our" Moroccan cat can only be the one we see it exactly where it is, at that exact point in the field of the shutter. Here photography approaches the idea of evidence, testimony of reality, but it also corresponds to the usual fascination human mind has with the millisecond of photography.

But we know that the millisecond is false, fictitious: it is an invention, a pure result of a clear intention and decision of the photographer. This frame is imposed, it forces us to believe that the instant captures something special, while the second later to the shot won’t belong to posterity. Şeyda is aware of this condition so well, that she is able to capture the instant besides her apparent unconcern with the classical composition and axis. The result is this mix of feelings when you look at her work: is she a random shooter or a great professional photographer? I’d say the fascination of her work comes from the unease caused by the lack of certainty on this question.

There is one final observation about the physical aspect of her photography. We noticed a deliberate choice to keep the irregularity of the white border on the edge of the negative frame, in the case of the Moroccan pictures, and she repeats it in other series. This choice seems to have a double meaning: first, it is a statement for the imperfection; secondly, the reaffirmation of "truth”, the faithful integrity of the negative: the "totality" of photography is there, there is no room for cutouts, edition or interventions on the composition, either during development or digital edition. The limits claim the irregular condition of photography, reinforce the idea of the fragility of the fiction created by the click. It is a representation of this imposture. This ragged edge, which rejects the clear orthogonal cutting is a flaw that forces us to mentally expand the picture beyond the imposition of the frame, unfolding a personal and enduring fiction about those extra millimeters of the instant photographed.

about the author

Flavio Coddou is an architect (1998) and is one of the editors of Vitruvius Spain.