“Is Warsaw becoming a city of the ‘Third World’?”—asked the sociologist Bohdan Jałowiecki in 2006. If the city was moving in that direction, Polish architects and planners might have already been well equipped to deal with it. This is because those among the most active today know the cities of the ‘Third World’ from first hand experience in the 1970s and 1980s, when intellectual labor was one of Poland’s top export products. Working in Algeria, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Syria, and the United Arab Emirates gave Polish professionals an acquaintance not only with advanced technologies, materials, and functional programs, but also with postmodernism as the new tendency in architectural practice and discourse. The postmodern appropriation of traditional urbanity and the rejection of architectural “utopias” of the early 20th century avant-gardes was as popular with the regimes in Baghdad, Damascus, Tripoli, and Abu Dhabi in the 1970s and 1980s, as with investors and large parts of the public in Poland after socialism.

The export of architecture and planning was a source of pride for socialist Poland, feeding into the Eastern Block’s political and economic support for the newly founded states in Africa, Middle East, and Asia. Capitalizing on the post-war experience of the reconstruction of Warsaw, Gdańsk, and the construction of new towns such as Nowa Huta and Nowe Tychy, Polish architects and planners contributed to modernist architecture and functionalist urbanism becoming a global idiom in the 1960s. This included such key projects as the master-plans of Baghdad (1967) and Aleppo (from 1962), administrative buildings in Kabul, museums in Nigeria (from 1969), and the trade fair in Accra (1967) followed by governmental buildings in Ghana.

The political motivations for this engagement had been shifting in the course of the 1970s towards economic ones for the Polish regime was in constant need of hard currency to pay off the loans taken at the beginning of the decade. The exacerbating economic and political crisis of real existing socialism was paralleled in Poland by a disillusion with “real existing modernism.” The failures to reform both of them were experienced by many Polish architects as interdependent, with architecture and urbanism subsumed under the requirements of state building industry and bureaucracy apparatus.

This disappointment with modernism resonated with the critique of undifferentiated spaces of post-war urbanism, prevailing in Western Europe and the United States, and with the rise of postmodernism, inspired both by American consumer culture and the rediscovery of the historical city in Europe.

Yet with the exchanges with the West being restricted, filtered, and increasingly unequal, it was the experience of working in the Middle East and Africa that furnished many Polish architects with testing grounds for new ideas. They included a search for urbanity by a reference to historical precedents, from the casbah to the 19th century European block; the redefinition of architectural practice as the production of images rather than of spaces; and the recourse to established visual and behavioral patterns—topics which became decisive for architecture in Poland after socialism. The experience with modern building processes, from CAD, through construction technologies, technical equipment, advanced materials, and functional programs, to the organization of the office, and contacts with international developers and construction firms became major assets after 1989. No less important was the confrontation with questions of disciplinary identity and the limits of architectural agency within the processes of production of space in liberalizing market economies.

These topics do not add up to a unified design strategy, but rather identify tendencies in architectural culture since the 1970s. They are addressed in this exhibition by a juxtaposition of projects for the Middle East and North Africa with selected buildings designed by the same architects in Poland after 1989. The framing and the selection of details stress the relationship between the building and urban space, from historical centers to suburban neighborhoods. Recognizing the relationship between the building and the city as the specific realm of architectural decision, this exhibition questions the responsibility of the architects for Polish cities after socialism.

notes

1

Wroclaw

The design of the church of St. Mary Queen of Peace in the Wrocław neighborhood Popowice resulted from a competition won by Wojciech Jarząbek and his team (1980). During the design and construction process (1980–94), Jarząbek travelled many times to Kuwait. The influence of this experience is legible not only in the quotes from his Kuwaiti projects, such as the Al Othman Center, but also in the interior of the church, experienced by many inhabitants as “oriental” in character.

2

Warsaw

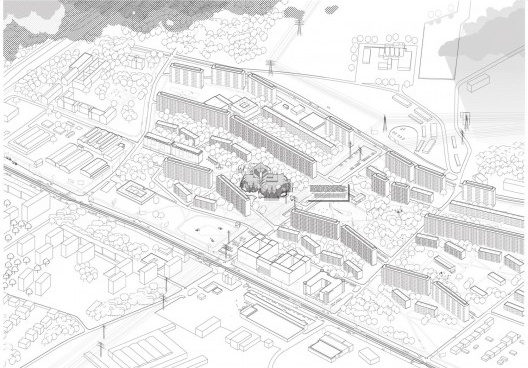

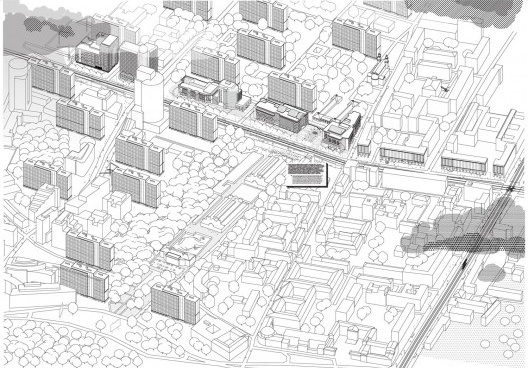

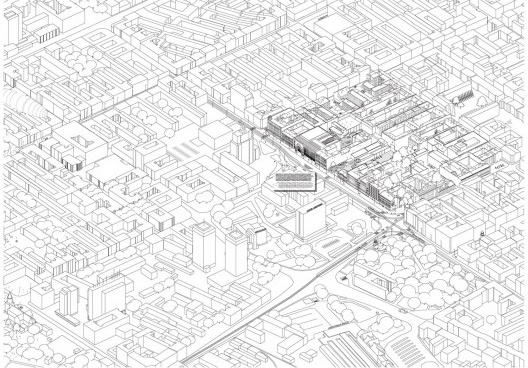

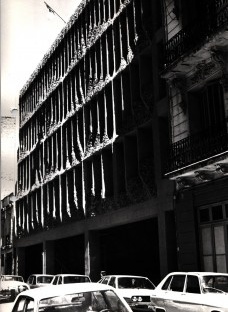

The four buildings of the Atrium Complex, designed by Andrzej Ryba i Tomasz Kazimierski (1994–2002), count to the first office and service centers in Warsaw after 1989. The contacts between the architects and the investor—the international construction and development company SKANSKA—go back to the 1980s when the company employed several Polish architects in Libya. The volumes, scale, silhouette, and details of Atrium refer to the socialist-realist estates at the Jan Paweł II street. Cutting across the functionalist housing estate Za Żelazną Bramą (“Behind the Iron Gate”, 1965–72), the Atrium complex feeds into Andrzej Ryba’s research of recognizable urban spaces, tested in his several projects in Syria in the course of the 1980s.

3

Nowa Huta

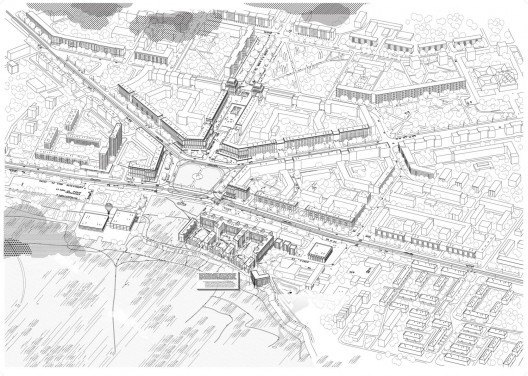

The Centrum E housing estate in Nowa Huta, the “first socialist city in Poland,” resulted from a competition won in 1988 by the team of Romuald Loegler. Completed in 1995, this estate refers to the urban plan of the center of Nowa Huta, designed in the style of socialist realism. This pertains to the division of the facades, the layouts of the courtyards, and the street sections. The search for historical precedences was exercised by Loegler already in his Syrian projects, including the project of the commerce and service center in Aleppo (1984).

4

Lodz

The Artur Rubinstein Philharmonic in Łódź was completed in 2004 according to the design by Romuald Loegler and his team. Among Loegler’s numerous experiences abroad since the 1970s a particular role was played by his work in Syria, where he was designing public facilities in Homs and Aleppo. In the façade of the auditorium in Aleppo, the raster of the cladding defines fields filled with references to local architectures. A similar procedure was employed in the philharmonic in Łódź whose façade becomes a display of the building previously occupying its site: the Ignacy Vogel concert hall.

about the exhibition

Curators: Piotr Bujas, Łukasz Stanek

Research: Piotr Bujas, Alicja Gzowska, Aleksandra Kędziorek, Łukasz Stanek

Drawings: Michał Bartnicki, Maciej Bojarczuk, Tomasz Chmielewski, Dorota Flor, Michał Grzegorczyk, Tomasz Janko, Franek Ryczer, Filip Surowiecki, Agnieszka Szymczakiewicz

The exhibition “Postmodernism Is Almost All Right. Polish Architecture After Socialism and the Postcolonial Experience” curated by Piotr Bujas & Łukasz Stanek (Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, October 1-30, 2011) follows the exhibition "PRL™. Export architecture and urbanism from Socialist Poland", (Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, 2010) curated by Łukasz Stanek.

about the author

Łukasz Stanek graduated in architecture and philosophy after studies in Kraków, Weimar, Münster, and Zurich. After his doctorate at the Delft University of Technology and fellowships at the Institut d’Urbanisme de Paris and the Jan van Eyck Academie, Maastricht, he is currently affiliated to the Faculty of Architecture, ETH Zurich. He is the author of Henri Lefebvre on Space: Architecture, Urban Research, and the Production of Theory (University of Minnesota Press, 2011) and of articles in books and journals, including LOG, HUNCH, and Haecceity. His projects were funded by the Mondriaan Foundation (Amsterdam), the Fonds BKVB (Amsterdam), the Swiss Science Foundation (Bern), the Adam Mickiewicz Institute (Warsaw), and the Graham Foundation (Chicago). Łukasz Stanek was recently awarded a Post-Doctoral Fellowship at the Canadian Center of Architecture in Montreal (2011) and the 2011-2013 A. W. Mellon Post-Doctoral Fellowship at the Center for Advanced Studies in Visual Arts (CASVA) at the National Gallery in Washington.