‘Fifth Year (Thesis) Design’, fall 2001. “The Sphere” was a collaborative (25 students) design and construction within a hypothetical sphere analogous to a particular subway route in Manhattan and Brooklyn. Cooper Union. [lebbeuswoods.net]

Corrado Curti: Feynman said that science can be seen as: “the result of the discovery that it is worthwhile rechecking by new direct experience, and not necessarily trusting the [human] race['s] experience from the past” in his discourse dedicated to What is Science?² In 1966. Karl Popper on the other hand, in The Logic of Scientific Discovery³ , wrote: “we shall have to get accustomed to the idea that we must not look upon science as a “body of knowledge”, but rather as a system of hypotheses, or as a system of guesses or anticipations that in principle cannot be justified, but with which we work as long as they stand up to tests, and of which we are never justified in saying that we know they are “true”. Although architecture cannot be considered a Positive Science, these definitions could be appropriate for architecture too. To what extent, and how, can scientific thinking be applied to Architecture?

Lebbeus Woods: Science on the level Feynman and Popper refer to is highly speculative and creative, relying on imaginative people to give it some new and original form. There is plenty of lesser science that simply recasts and reshuffles things we already know to put a finer point on it. Architecture is much the same.

There is the everyday architectural practice that recasts and reshuffles the already known - office buildings, housing projects, shopping malls - that simply refine for tastes of the moment the familiar typologies, meeting the demand for something new, but not too new, that is, new to the point that we don’t feel comfortable with it, demanding that we have to change our habits too much. The upper, really creative levels of science are very inspiring, but only to architects who aspire to make a breakthrough, to solve a problem that has never existed before or has not yet been solved. For the other, everyday architects, this level of science is of little use or interest.

It’s important to understand here that there are, with respect to knowledge, crucial differences between science and architecture. Science presumes that there is some ‘truth’ that must be discovered and defined, say, the structure of the atom or the origins of the universe. All the creative types in science can get to work on such well-defined problems, or aspects of them. In architecture, there is no such equivalent truth to be found, defined, or understood. Architecture is existential. Its hypotheses and theories, the problems that it confronts are of the constantly shifting conditions of being human. While they may hold some basic human traits - physical and mental - the goal for architects should not be to enshrine these in eternal laws and forms, but to enable people to live to their full potential, whatever that is or may be. Scientific thinking can only be of limited help in this task.

CC: The term Experimental is so widely used in contemporary architectural discourse that it often becomes vague and generic. Today, various different approaches such as: the integration of software and informatics in design processes to generate and control forms, the introduction of new manufacturing technologies to building techniques and processes, and the application of innovative materials to buildings may all be referred to as experimental. During the course of your career you have researched into the possibility of establishing the field of Experimental Architecture as a distinct branch within the discipline. How do you define it?

LW: An experiment, simply put, is a test of an idea or a hypothesis, a ‘what if,’ to see if it works in reality.

An experiment is NOT the creation of the hypothesis - that belongs to the realm of theory. It is also NOT the application of its results to reality - that belongs to the realm of practice. The experiment is an in-between realm. It happens, to use the scientific term, in a laboratory - a personal space and under controlled conditions. In architecture it necessarily takes some spatial, visual form - drawings and models by hand and computer are most common. These can be evaluated post-facto by the architect and others regarding their confirmation of the hypothesis and also their potential usefulness in practice.

It has always seemed important to me to establish the experimental as a distinct activity in the field of architecture because of the changing nature of the field in the contemporary world. In the past, the role of buildings and the architects who designed them was clearly defined, because society itself was clearly defined in its hierarchical structure. There was little need for theory because people knew what buildings were supposed to do, the only variables being of style and arrangement of architecture’s already known, historically precedented components. Consequently, there was no use for the experimental or an in-between stage of design. Whatever experimenting the architect did was folded into the normal design process. There were no new hypotheses to confirm before the architect and a client committed themselves to full-scale construction.

But all this changed when our society - ever more global in scope and technological in character - itself began to change more and more quickly. There are new technologies introduced almost every day and these change the ways people live. Political and economic changes are happening almost as frequently. It seems obvious that the pace of change is accelerating to the point where the changes are qualitative and structural. The need for new kinds of space is growing, but architects - in their practices - don’t have either the temperament or the time to explore new possibilities. This creates the need for the experimental architect, who is devoted to such exploration. This is a historically new situation, and I believe that the field of architecture has yet to respond to it. RIEA, I have hoped, will create the example of what might be done.

notes

2

The famous discourse was originally presented by Richard Feynman at the fifteenth annual meeting of the National Science Teachers Association in 1966, in New York City. The text is fully available at: www.fotuva.org/feynman/what_is_science.html

3

Popper K, The Logic of Scientific Discovery, Routledge Classics, London 2002, ISBN 0415278449, A brief excerpt is available at: bio.classes.ucsc.edu/bio160/Bio160readings/Logic%20of%20Scientific%20Discovery.pdf

4

The First RIEA conference on Experimental Architecture was held at Emmond Farms, Oneonta, New York 1989, The First Conference featured: Peter Cook, Lise Anne Couture, Neil Denari, Godon Gilbert, Ken Kaplan, Ted Krueger, Hani Rashid, Micheal Sorkin, Micheal Webb, Lebbeus Woods

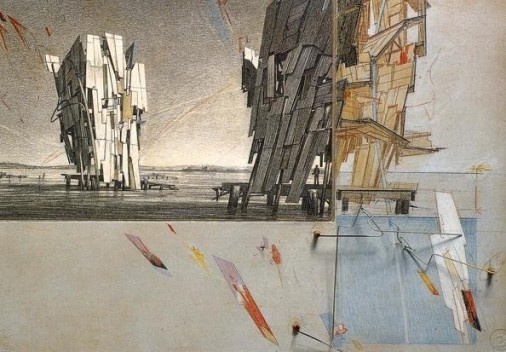

San Francisco Bay Project. Structures designed for an abandoned waterfront site on San Francisco Bay which use the energy released by the earthquake to ‘transform themselves’, 1995 [lebbeuswoods.net]