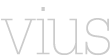

Icebergs, free-floating structures, 1991. Ocean shore and city of Long Beach, CA [lebbeuswoods.net]

Corrado Curti: Looking back at your early works we see a highly inspiring and refined formal research, while your recent projects adopt a more abstract visual language. At the time when you were working on projects like War and Architecture, La Habana Nueva, and Aerial Paris(5), mainstream architecture was still divided between “safe for capitalism” modernism and post-modernist decoration, while in the last 15 years formal explorations have given rise to hundreds of built and never-built urban icons characterized by extremely articulated, complex and varied shapes, often celebrating nothing more than the status of their affluent commissioners. Has this condition, where aesthetics and ethics are distanced, and self-celebrating formal research is pushed to unprecedented limits, influenced the shift in your recent works towards a cleaner and essential formal language?

Lebbeus Woods: I have always been driven in my work by a few questions, a handful of ideas, having to do with the changing nature of existence and its necessary, usually difficult, transformations. I chose architecture as my field of thought and work because it seemed to me to encompass the whole range of human experience and aspirations, and at the same time to be instrumental - literally a tool - that would be useful in our adaptation to change.

Over many years, the way that I have used the tool as an instrument of thought and action has naturally evolved. This is partly because of my own evolution and partly because our world has itself changed in its forms and dynamics. In earlier years I thought it was most important to visualize scenarios of new types of buildings responding to crises of change. More recently, I’ve turned to questions that are more about the possible structures of change itself, and how they might be manifest in tectonic - that is, constructed - form. In the earlier work, I wanted to reach a broad public; in the more recent work, my aim has been to address architects in particular.

You are right to judge that the flood of form-making due to the rendering capabilities of computers has made visualizing ‘the new’ seem to me much less urgent. I sometimes think that there is far too much of it now, and that, very often, spectacular imagery is used to dress up old ideas, or no ideas at all. In any event, my interest has turned elsewhere.

CC: Very often in architectural literature, the terms: Visionary, Utopian and Experimental, when used to describe works and projects, become blurred. Yet, if we are to compare Architecture with the Sciences, where the experiment is a way of observing and investigating reality in relation to hypothesis, this ambiguous terminology is highly misleading. Taking a closer look at your works, I think it is possible to grasp what distinguishes an experimental approach from merely visionary and/or purely utopian works of architecture. All of your projects are grounded into a very specific “terrain”, whether physical and/or conceptual, from which they stem. They are not evocative sketches of a positive, universal, displaced (un-grounded) solution: Panacea-projects or Ideal Cities. They are explorations of alternative architectural responses to very specific and often extreme conditions: the quake in San Francisco, the wall between Israel and Palestine, and the war in Sarajevo to name a few. The radical interpretation (the hypothesis) of such specificity allows the projects to become tools to investigate the architecture-reality binding (the experiment), and to push and extend the boundaries of architecture as discipline (the results of the experiment). Do you agree with this reading? What (other) methodological tools can be considered specific of the experimental approach in architecture?

LW: Your reading is reasonable. The only qualification I would make is that the conditions you describe have little architectural history for my experimental projects to be alternatives to! Architects have largely ignored earthquakes and other natural, if violent, transformations, political walls, and wars, feeling that they were outside of architecture’s proper domain, which is to design the known building typologies for the known and stable social conditions.

Instability or volatility has been considered the domain of politicians and humanitarian aid workers and the military and not the legitimate concern of architects. As one objector once said to me in a lecture on my work for Sarajevo during the war there, “We have fighter planes, don’t we? They will take care of it!” Oh, yes - it’s always a ‘they’ who will assume responsibility for the problems we don’t know how to solve.

This brings me to the methodology question you raise. We architects, in addressing the dynamic contemporary world need to adapt our habits of mind. Most importantly, we must go beyond thinking of architecture only as objects or products. Buildings are obviously important and necessary and we want them to be well designed, but at the same time they are only part of a complex human fabric that is being constantly woven and rewoven by many people, events, ideas. Architects need to see their work within this larger frame of reference and therefore need to develop broad points of view. This takes time and a continuous effort and commitment.

There is no ‘they’ who can do this for the architect. Architecture in this way is a very philosophical field, yet very personally philosophical, and strongly existential, not to be simply taken from philosophers and their books. Every really good architect develops - either visually or verbally or both - a coherent world-view. It is up to each how this is formulated, that is, what method he or she uses to express a personal philosophy. But it is very certainly depends on having a disciplined method of doing so.

'The Wall Game', Dialogical Architectural game, Israel, West Bank, 2004 [lebbeuswoods.net]

CC: Looking at your recent projects and installations - La Chute, The Storm, The Wall Game(6) - it appears to me that your investigation directly addresses issues like: indeterminacy, change versus permanence, space as the result of a dynamic field of interactions rather than fixed formal definition, architecture as the product of a set of “rules of the game” rather than the direct materialization of a project. What role do these concepts have in your research, and how relevant do you consider them to be in relation to the future development of architectural research?

LW: As I said, making new forms as such does not seem a high priority for me, as it once did. This does not mean that there no longer exists the need for ‘a new architecture.’ Actually, that need is more urgent than ever, as human society evolves in its forms and needs in an accelerating way. Nor does it mean that we do not need entirely new types of buildings - which was always the focus of my work. It does mean, however, that what is truly new will emerge from new concepts of living and of space and of design processes. New ideas. New ways of thinking and working. New approaches to designing. Of course, forms are important, but they can no longer be imposed on conditions. Rather, they will emerge from the new ideas and design methods.

The more recent projects of mine that you mention experiment with this hypothesis. No ‘finished’ or ‘final’ form was envisioned from the start and indeed does not exist. The forms of the spaces and their defining elements were not designed in the traditional sense of the term, but resulted from the direct engagement with particular material conditions. This approach turns away from ideas of the architect as a ‘master builder’ or an ‘auteur’ controlling the ultimate results. The architect must still exercise control and take responsibility for choices, but over (as you call it) the rules of the game.

In this way the shaping of the human environment becomes more democratic, more open to the input of many people involved in building, more a fertile ground for really new ideas. Oh, yes, it’s risky - these projects did not result always in spaces I liked, or would have preferred according to my own tastes, but that is the price of experimentation and, I’m sure, of a more daring and demanding human future - if we are to meet it creatively.

CC: What projects are you working on, right now?

LW: I’m mostly writing and teaching - the two are intertwined. My blog is a major project, taking a lot of my time and interest. The online space is an emerging world of many new dimensions. I’ve only begun exploring it. As for design projects, there is at the moment only the Light Pavilion in Chengdu, China, which is currently under construction.

notes

5

Projects, Works and Bibliography by Lebbeus Woods can be found at lebbeuswoods.net

Civilization. Installation in the exhibition “Seven Hills: Images and Signs of the 21st Century”, 1999-2000. Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin, Germany [lebbeuswoods.net]