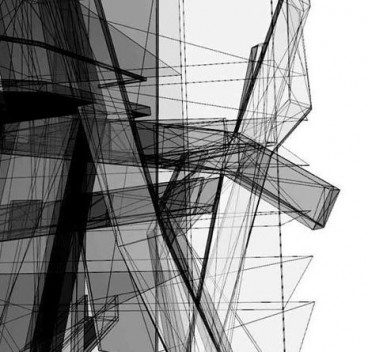

Preliminary design for a Technological Pavilion, to be built within a mixed-use project by Steven Holl Architects. Chengdhu, China. Lebbeus Woods in collaboration with Christoph A. Kumpusch, 2007 [lebbeuswoods.net]

Corrado Curti: What are the most urgent fields of research that Experimental Architecture should engage in today, and in the immediate future?

Lebbeus Woods: The most critical and difficult problem is the rapid growth of cities. The widening gap between the poor and the rich means that much of this growth is in the form of slums and other kinds of unsustainable – in human and environmental terms - newly built urban landscapes. Architecture can’t directly affect the economic disparities, but it can refuse to cooperate with the social institutions that create them. Also, architecture can propose the best possible solutions to slums and deteriorating urban conditions, and not only those that serve prevailing political and economic powers. This is because RIEA does not depend on those powers for its existence.

Certainly, there is a great need for low-cost housing - for housing the growing urban populations. I’m sure that the term ‘housing’ has to change, because it is a typology based on rigid social categories that are today outmoded. Housing meant ‘mass-housing’ for masses of workers employed on factory assembly lines, originally in the form of ‘company towns.’ Later, housing ‘projects’ were designed and built for masses of lower-income urbanites, an underclass that still exists but is much too diverse to be massed together and in effect ghetto-ized.

Today’s increasingly service-based economy, one fragmented by computers and internet niches, has created a need for an entirely new typology of living quarters and their groupings, one that has yet to be invented and tested. This is priority for experimental architects.

Another priority - an even more difficult task - is how to improve the living conditions in existing slums. The best thing would be to eliminate slums - the ones existing today - and make sure no more are built ever again. But this would require the elimination of poverty. Not only is that way out of any architect’s domain, but it’s a task that society as a whole must be committed to achieving - a commitment that has not yet begun to be made. Until it is - if it ever is - architects can and must look for ways for strategies and techniques that slum-dwellers can use to help themselves, if necessary a small step at a time. Something will be better than nothing - which is more or less what’s happening today - architects don’t want to get near the problem.

Finally, for now, I would say that architects who want to explore the most cutting edge issues must confront the relationship of aesthetics - the way things look - to ethics - what things mean in the most fully human sense of the term. Consumerism and mass-marketing have ghetto-ized architects, and especially the most visually talented ones, as product designers, stylists who dress-up conventional products to make them more marketable or simply serve as a form of prestige advertising. Breaking out of and away from this captivity is the highest priority challenge to the field of architecture. What makes it difficult is that architects must develop their social commitments without sacrificing their aesthetic ideals.

It’s not sustainability or beauty, practicality or poetry, but both that have to be accomplished, at the same time, in total harmony and support of each other.

Preliminary design for a Technological Pavilion, to be built within a mixed-use project by Steven Holl Architects. Chengdhu, China. Lebbeus Woods in collaboration with Christoph A. Kumpusch, 2007 [lebbeuswoods.net]