In the beginning, Thiago Bernardes asks two questions in relation to his grandfather’s work: Why are we doing this film? Why did they stop talking about him? Throughout the movie we try to find the answers, but further questions and complications soon emerge, as it becomes clear how closely related these initial two questions really are. To answer to the first question, it is necessary to answer to the second.

Architecture is engaged with politics. The word politica itself is descended from the word polis – the Greek word referring to the ‘city state’, and the words urban, urbanity or urbanism are descended from urbs. The polis and the politica, the city is inherently political. Architecture and politica have an intimate relationship and mutual aim; they naturally bond to each other as tools for a transformation, a collective transformation. The documentary Bernardes has the wonderful quality of reminding us, once again, that the architect deals with society to bring about transformation. If we consider such an urge to transform as inconsequential, ingenuous or even irresponsible, it is probably because we have become used to perceiving politics as mere diplomacy, or a tool of self-promotion, and architecture as a service or a technique, hidden in webs of bureaucracy, or even architecture as an autistic discipline focused proudly upon itself.

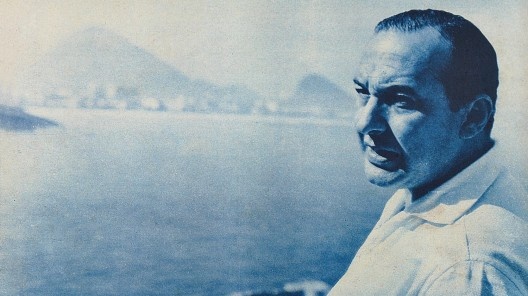

Rio Future Plan, 1965. Architect Sergio Bernardes

Imagem divulgação

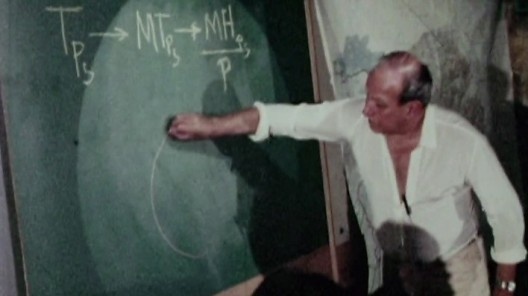

Sérgio Bernardes was an architect who challenged the limits of the profession. He devoted great care to the territory, envisioned the future and was willing to propose and promote major shifts in society. His driving force was to go ever further. He believed that architecture should not end in the “know how” but rather in the “know why”, which is a way of saying that it should not just respond to a program but that it should create the very program itself. In his LIC – Laboratório de Investigação Conceptual, a conceptual research lab, built within his own studio in the 1980’s –, he takes a step forward towards a transdisciplinary approach. He creates a body of well-informed research insights across the entire Brazilian territory, and develops strategies of speculation on even larger planetary scales, but he acts and uses this research for the unique purpose of building (transforming), in support of his belief in the power of architecture as an agent of change. Because of that crucial drive for transformation, he managed to cross the threshold between politics and architecture, becoming a politician himself. But even as a politician he could not abandon the architect’s role, and that is probably why he lost the elections for mayor ofRio de Janeiro.

Rio Future Plan, Copacabana, 1965. Architect Sergio Bernardes

Imagem divulgação

But still, the question of why Bernardes remains invisible is unanswered. In modern times, alongside the heroic vision of the architect as public servant there have been several examples of architects’ collaborating with military dictatorships. We could bring up the case of Corbusier inAlgeriaas one of the most well-known. But this movie’s greatest contribution to architectural debate is its dissection of the process by which architects and architecture are validated – how the academic canon is constructed or how the narratives of the winners overlap with those of the others. What makes it possible to erase some figures from history, whilst highlighting others? And is this not also how history as a whole is created? I was always surprised to have discovered the work of Pancho Guedes, and other Portuguese Modernist architects that had been building in Portugal’s colonies of Angola and Mozambique during the dictatorship of Salazar, not in Portugal (where I studied architecture, and these figures were ignored) but in Holland, where they were admired. History and narratives are made by and in the nets of power, the corridors of influence and the salons of the winners. By understanding the history of power, we can uncover the nature of history itself.

“While the word politics suggested the idea of surface and the superficial, the word power evokes center and depth. Surface history having lost its charm, political history becomes history in depth by becoming the history of power”.

Jacques Le Goff, 1971

For all these reasons, this movie will certainly encourage important research and debate, and will contribute to the rewriting of the story and history of a forgotten part of Brazilian Modern architecture.

But aside from all this, at the end of the day, this movie is also simply a tribute to a great architect; a beautiful love letter from all who loved him and got inspired by him. This homage aims to infect the spectators by osmosis. Probably, and hopefully, some students of architecture and some politicians will get inspired too, but the film will especially contaminate those who, like Sergio, are endless dreamers, researchers and inventors of the future. We must look further. This is the lesson of the man without a past, and the answer my friend is blowing in the wind.

note

NE – This text was originally commissioned by The Architecture Foundation to accompany theUK premiere of the documentary Bernardes, as part of The AF series Architecture on Film.

production credits

film

Bernardes

direction

Gustavo Gama Rodrigues e Paulo de Barros

year

2014

time

1h31min

argument

Thiago Bernardes

screenplay

Gustavo Gama Rodrigues, Paulo de Barros e Yan Motta

photography

Stefan Heiss e Paulo de Barros

about the author

Pedro Campos Costa; a Lisbon-based architect and the curator of Homeland, which saw the Portuguese Pavilion manifested as a newspaper for the 14th Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia (2014).