Chicago is the city of the architect Mies van der Rohe, the structural engineer Fazlur Khan (SOM) and Louis Sullivan: they all have streets named after them in a country where the streets and avenues always have toponymy of ordinal numbers. (An important reference for Brazil, a country where over 30% of the projects under process in town-councils are proposed to honour unheard people with street names – compound names often with three or four surnames.) Chicago is the birthplace of the skyscrapers – the Auditorium Building, the Sears Tower, the bizarre Chicago Temple with its neogothic church on the thirtieth floor and, the best of all, the John Hancock Centre by Fazlur Khan. In recent years, the city has been celebrated for its new architecture, like the Jay Pritzker pavilion and the BP Bridge by Frank Gehry, the bean by Anish Kapoor and the extension of the Chicago Arts Centre by Renzo Piano.

After seeing all this, I went to the Loop (the centre) to see three Mies queued at the Federal Centre, then to the lake Michigan to see its Lake Shore Drive Apartments, and then to the Chicago river to see another Mies (IBM Bldg.) right beside the beautiful towers of the Marina City. I ended up at the Illinois Institute of Technology, a university campus entirely designed by Mies (I still needed more as I prefer the horizontal to the vertical Mies).

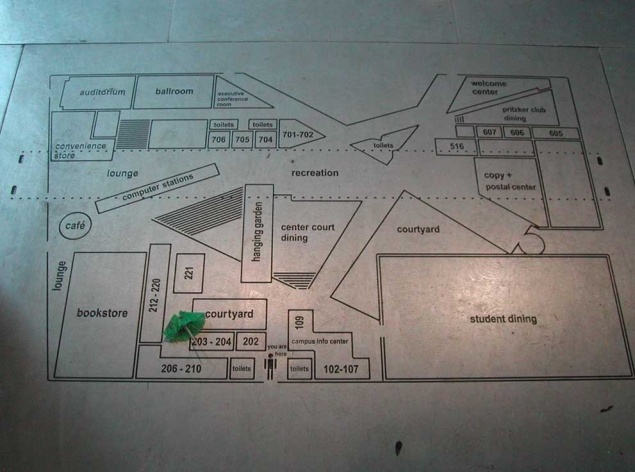

“Issue: re-urbanize the void”; “to re-urbanize: occupy largest territory with least mass to create urban liveliness”. The legend says that when Koolhaas began to project the MacCormick Centre, he made many students map the ways through which the students strolled in the campus. Until then, the building site – a void under the overpass of the underground green line that bisects the campus in two – was an uncomfortable gap between the dormitories of students from one side of campus buildings and classrooms on the other. These spontaneous routes were endorsed and used as the main corridors of the Centre, leaving the spaces between the aisles as program islands; each with its own identity.

The dubiously annoying aspect of the building is its not-very-delicate relation with its neighbour, the Commons Building, Mies’ old student union that had been awarded by the American Institute of Architects in 1953. The attack is explicit: with so much space available on a campus defined as “a void inside a void”, two buildings that could be tens of meters from each other are as close as semi-detached houses (despite have been built in a sea of open space). The external walls of the Commons turned into the internal walls of the McCormick, and the covered part of one covers the other’s in an obscene gesture that, even having awoken the rage of all the bureaucrats of the Illinois heritage institute, was built to the original project. (The original proposal also predicted the extensions of the routes into the Commons Building body, but that was not built.)

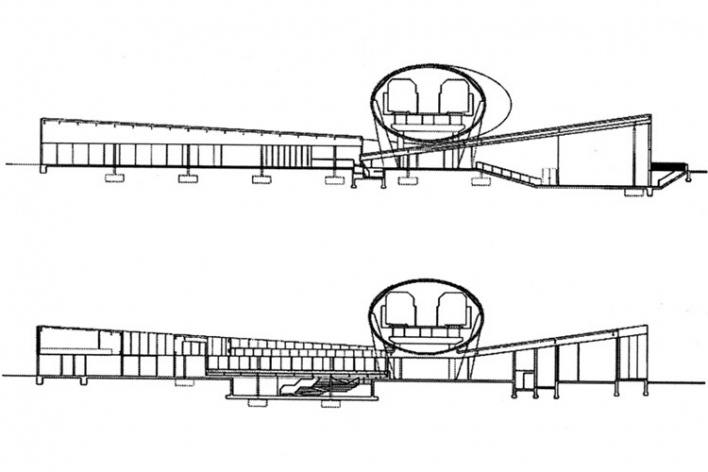

Ambiguities attenuate this offense. A huge portrait of Mies stamps one of the MacCormick entrance doors, and the pillars of the Barcelona pavilion are used as its main structure. However, they were mixed with the harsh concrete columns of the underground viaduct that fall without any embarrassment amongst Mies’s columns, which also suffer with the intromission of another, third group of pillars (the diagonals of black concrete supporting a metal tube, or Exelon tube, that envelops the viaduct to absorb the noise of the trains). Moreover, the architecture, instead of denying the presence of the elliptical Exelon, let it serve as an element that divides and flattens the roof in two. This are two inclined planes which, taken together, make the building a bizarre situation where the roof seems to have been forced down awkwardly and inserted below the Exelon tube; something that caused the combination of a tube and two roofs in a seemingly accidental way.

A section of the building makes clearer the impression that the presence of the roof is even accidental: one of these slopes is so low when "stuck" under the Exelon that it provokes an interstitial, useless space due to its ceiling height too low; a fact found in other works of Koolhaas where the logic of functionalism is intentionaly broken.

According to Anand Narinder Singh, a student who guided me through the IIT, another legend says that due to budgetary reasons the material of the celing had to be changed as the cost of the Exelon was 13.6 million against a budget of 2 million. Light green sheetrock panels substituted what would be elegant wooden wainscots. The joints between the panels were left without covering; a non-finished lining with the marks of the grouting badly placed exposed: “(…) this is a return to Mies’ Puritanism in relation to steel, but in a more abject material”, said the architect in an interview, confirming the Indian’s information.

Nowadays nobody denies Koolhaas’ influence and his ability to mix contextualism with a certain narrative allegory. But I got surprised in knowing that Brazilian architects are not the last modernists in the world; the IIT students are. A few metres from the MacCormick is the Crown Hall, one of Mies’ most famous works and where the school of architecture is. There I saw tens of models at one side of a studio room. “Are they Mies’ villas?” - I asked my guide. “No, he answered solemnly, they are projects of our fourth grade students.”

about the author

Carlos M Teixeira is graduated at EA-UFMG and had his master in urbanism in the Architectural Association. He published the books “História do vazio em BH” (CosacNaify), “Espaços colaterais (cidades criativas)”, “O condomínio absoluto” (C/Arte), and is partner of the Vazio S/A office.