First I would like to thank Professor Maria Lucia Gitahy, coordenadora do Grupo de Pesquisa em História Social do Trabalho e da Tecnologia como Fundamentos Sociais da Arquitetura e do Urbanismo (HSTTFSAU), for inviting me to participate in this seminar. This essay partly results from my participation in the symposium held at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth (UMassD) to celebrate its campus’s 40th anniversary. During this event, workers and architects involved in the original project, scholars from different institutions; faculty, staff and students from UMassD; and community representatives met to share their experiences and reflect on the socio-economic, technological, and historical significance of the campus’s architecture and urbanism. (2) The illustrations presented here include some of the 420 drawings Paul Rudolph selected and donated to our school in the 1980s. (3)

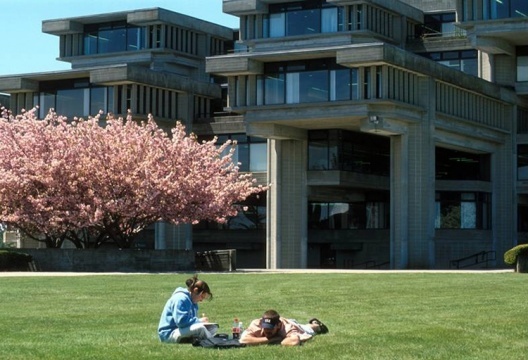

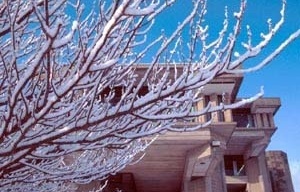

Located in southeastern Massachusetts, the campus of the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth (UMassD) is the largest of architect Paul Rudolph’s works in the United States. Initiated in 1963, during Rudolph’s six-year tenure as dean of Yale architecture school, its first building was completed in 1966, when it already raised contradictory reactions. For some, it proclaimed the construction of the most genuinely modern campus in the U.S., whereas for others it represented the most appalling and sinister grayish architecture. Whatever the reaction, Rudolph’s vision for the campus evoked a strong response then as it does now. Today, these pungent responses are immersed in a peculiar cultural context very well illustrated by the media. In the past months The New York Times Magazine has devoted many different editions both to modern architecture and to the baby-boomer generation that grew up under its spell. In one of the magazine’s special editions, journalist Stephen Hall struggled to make sense of aging to a generation raised to believe there is nothing but youth. (4) Another magazine exhibits Oscar Niemeyer’s Copan Building façade in its cover to illustrate an article, “Concrete Jungle,” which deems São Paulo (misspelled São Paolo) cool in its “dense politically modern urban landscape,” and a more recent issue highlights the modern works of “Paulista social engineer” Paulo Mendes da Rocha. (5) All those links suggest the need of a more refined work weaving architecture, modernism, Brazil, and the United States. For the purposes of this paper, they provide the impulse for our short reflection on modern American architecture and the aging of one of its most exemplary representatives: the educational campus. By the mid-1960s, during the peak of modern influence in the United States, baby boomers were starting to attend college. UMassD was one of the many institutions built across the country in this period to house this new generation. Today, the students of the sixties are part of a “new” generation of middle-aged people whose buildings from their college years are either facing destruction or needful of means to cope with aging. The way Paul Rudolph’s middle-aged campus is re-interpreted in the twenty-first century is a window onto our understandings about twentieth-century identity and urbanism. This paper explores those ideas in three main sections. First, it introduces the historical context and the architect, and then it focuses on the project to bring in its significance to the region. The final part reflects on the former and current uses of the campus and on this project’s quest for a new insertion in its twenty-first setting.

I. Paul Rudolph, the Architect

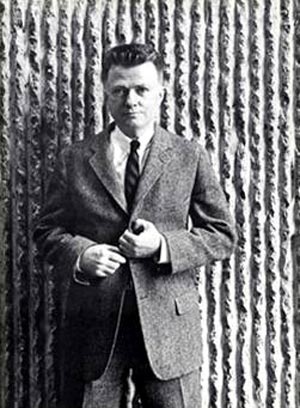

A Kentucky-born architect and the son of a Methodist minister, Paul Marvin Rudolph (1918- 1997) did his undergraduate architectural studies at Alabama Polytechnic Institute, graduated in 1940 and briefly worked in Sarasota, Florida for R.S. Twitchell, and between 1941 to 1949 he studied at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD), did three years of service in the Naval Reserve (New York Naval Shipyard), and visited post-war Europe as a Harvard Wheelwright Traveling Fellow. Though his precocity had been immediately recognized by Walter Gropius, the head of the Architecture School, Rudolph spent little time at Harvard. World War II interrupted his education and he served in the navy yard before graduating just one semester after the end of the war. (6) Recognized as one of the most talented of Gropius’s students, he received a prestigious fellowship to go to Europe right after his graduation. On his return from Europe, he rejoined Twitchell in Florida this time as his partner. In the late 1940s, Rudolph, still a devotee of Wright, (7) innovated by adapting European modern ideas to his Beaux-Art language and applying it to the warm weather of the south. In the burgeoning vacation-beach house market, Rudolph’s experimental architecture soared. (8) One of Gropius’s most prized and successful students, Rudolph sought to go beyond his masters in his quest for his self-expression. Rudolph’s vocabulary incorporated a range of influences – from Wright to Mies van der Rohe – as well as a close research of different experimental materials. (9) Technologically expressive and daring, Rudolph became increasingly experimental. By 1952, when he opened his own firm, he firmly criticized the preoccupation with functionalism and the universalism of the international style.

As a leading critic, in the mid-1950s, Rudolph passionately fought the increasing cultural conformity of the post-war years and the current state of modern architecture. He demanded a turn to the vernacular and a space that took into consideration the psychology of the individual. (10) He stressed that monumental architecture could open space, challenge, and guide the individual. According to Rudolph, structures had the power to move you forward and to affect people psychologically. In 1954, Rudolph participated in the Young Architect Competition in São Paulo, Brazil, where he won first prize. (11) Rudolph’s first opportunity to try out his ideas came in Massachusetts during the economically secure and prosperous late 1950s. His first large-scale public project was the Mary Cooper Jewett Art Center of Wellesley Campus (1956-1958). (12) From 1958 to 1965, he was chairman of the architecture department at Yale, when he had the opportunity to design the Art and Architecture Building of the school (completed in 1964), which put Yale in the international architecture circuit. This was when he was commissioned to build the whole university compound of what is today the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth.

II. UMassD, the building

Historical context

In 1963, the Massachusetts state legislature appropriated money to unite two existing institutes – the New Bedford Institute of Technology (NBIT) and the Bradford Durfee Institute of Technology (BTI) – into a new educational institution: the Southeastern Massachusetts Technological Institute (SMTI). (13) SMTI would evolve into the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. SMTI’s first president, Joseph Leo Driscoll headed the plans for the new campus in North Dartmouth and Paul Rudolph, one of the leading architects of the day was engaged to build it. (14) Timothy Rohan explains that the architect “was one of the central figures of postwar American architecture [already] famous for his highly textured surfaces and unique rendering style” (15). The UMassD campus was a state project, the money was appropriated in 1963, and ground was broken for the first set of buildings (Group I) on June 14, 1964. (16) Half way through the campus construction, in 1969, Paul Rudolph’s role ceased and architect Gratten Gill carried out Rudolph’s master plan, under immense pressure, until the last building, the library, was finally opened in 1972. (17)

The plan was immersed in a climate of optimism that surrounded the discipline of architecture in the early 1960s. This was the time when Gropius experimented with the production of mass-produced houses in places like Lincoln, Massachusetts, although still using a language representative of European modernism. President John Kennedy fostered a cultural renaissance, which mirrored a broader political discourse of vigor and renewal. (18) American schools and universities argued about the experience of art and its formal features. In the early 1960s, modernity and progress were believed to be synonymous, and modern architecture was the grammar of the campus. The UMassD campus’s architecture is considered “brutalist:” Its large-scale, twisted buildings lead to a dramatic, even at times overwhelming experience. Brutalism is a design form of attitude, a post-World War II response to the criticism of certain facets of the international style deemed to alienate people in its monotonous uniformity, which did not enter into dialogue with other buildings and the environment around it. A brutalist posture kept the modern vocabulary (modular glass, great height, few interior supports, and large interiors) but incorporated the recent technical advancements, which challenged the staid, clean lines of the international style and demanded an appropriate expression for the new political and cultural context. (19)

In the mid-1960s, UMassD was considered one of the most accomplished exemplars of modernism in the United States. But this view has evolved, and in what follows I review three distinct visions of the modern. The first vision is from when UMassD was being built and Rudolph’s cool experimental architecture brought to the fore the vital roles of concrete and drawing. The second vision relates to the early 1970s during the transition to a new socio-political era in American history, when Rudolph’s buildings became synonymous with “politically incorrect” spaces. The concluding section explores the interplay between the first and second visions in the past and the present-day emphasis on renewing and reinserting the modern in the urban fabric.

The vital role of concrete

Why concrete? When asked why he had chosen a pre-cast concrete façade for his Boston Blue Cross Blue Shield Building of 1957, Rudolph replied that he preferred “buildings that respond to light and shade to buildings that are all reflection” (20). Rudolph’s opaque concrete walls suggest an active response to the environment, whereas mirror-like curtain walls would passively reflect it. (21) The corrugated surface:

Broke down the scale of walls and caught the light in many different ways because of its heavy texture. Light was fractured in a thousand ways and the sense of depth was increased. As the light changed the walls seemingly quivered, dematerialized, [and] took on additional solidity ... When light hit the rough-cast, low-relief finishes, the ever-changing play of shadowed patterns across the surface softened the impact that the imposing concrete mass of the building had upon its surrounding. At the same time, the elements would weather the surface… (22).

UMassD’s master plan exemplifies Rudolph’s experiments with reinforced concrete. Concrete was the language of the project and the key to the human architecture he was looking for. He was moved by concrete and his brutalist attitude is shown in his familiarity with this building material. (23) He pours it in forms and ridges, and the wooden forms are taken away to get a variegated result. The poured-in-place concrete produced the vertically striated surfaces, which created the impressive dramatic space. (24) The concrete, whose texture originated from local materials, was used everywhere in the buildings. The textured, enveloped structures flow over and above the ground. In order to create contrast, he made use of an omnipresent colorful (orange, originally) carpet. For Rudolph:

Color is one of the most complex things in the world because it’s always so different in different lights, different quantities at different times of the day, and when juxtaposed against other colors the actuality and the appearance are two different things … One of the aspects of color that fascinates me is the reflected light from color. I have worked with concrete … and I would make a very warm-toned carpeting.” (25).

Rudolph’s fantastic concrete creations derived from those incredible surfaces and rendered his hallmark: a technologically expressive modern architecture. Rudolph’s version of brutalism, which was to be followed by other architects, produced elaborate silhouettes that formed the basis for its appeal. (26) Concrete dictated the special flow through interior volumes. The vertically poured concrete forms weaved the leitmotif within the UMassD buildings. Among the many adjectives critics have mostly used to depict the resulting surface are collage-like, intensely worked, highly textured, corrugated, tactile-quality, and brutal-quality. All those adjectives also depict a paradoxical surface which simultaneously attracted as well repelled touch. Such qualities emphasize the material’s tactile and optic traits as well as impart a controversial architecture whose strong dramatic presence requires per formative, expressive gestures from its users.

Concrete, the ever-present textured surface, turned in Rudolph’s hands into a form of low relief, an ornament. These concrete walls are graphically expressionist, a shattered irregular surfacing with a linear woven textile quality. As Rohan notes, this process of the rendering of surfaces with multiple parallel lines “translated directly into the construction of surfaces with a similar appearance,” (27) which conformed the image to the drawing.

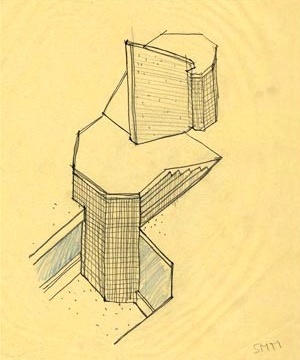

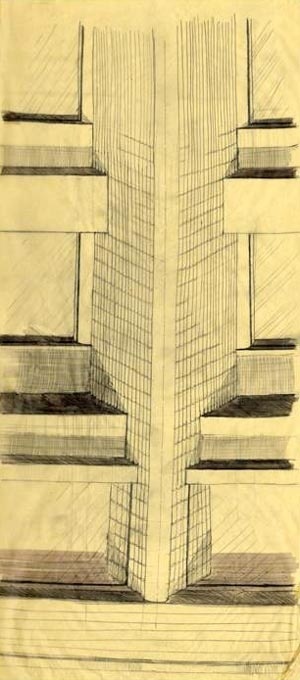

The vital role of Rudolph’s drawing

A defining characteristic of Rudolph’s drafting style is the almost obsessive attention to line and detail, especially in relation to the rendering of material surface … for Rudolph the graphic work existed as an end in itself, a place for expanding the discipline and capacities of architecture (28).

Under his brutalist method, Rudolph called for an aesthetic that fused drawing and building. In his concern with visual design, Rudolph was one of the few modernists of his time “who stated that the Beaux-Arts was worth reconsidering for the ways in which it had approached the design of the city” (29). And since urbanism was a central problem for Rudolph during the 1960s, UMassD concretely expressed those concerns. At UMassD, Rudolph played with the placement of the concrete casts, using them in sometimes unexpected spots – such as on stairways – and throughout the building; an experience that provokes an ever-flowing feeling.

This playing with forms also resulted in labyrinth-like interiors: Rudolph was a master at multiplying levels. Within many three-story buildings, he managed to nest more levels of interlocking spaces divided by bridges, walls of concrete, and glass. The extensive use of walls, floors, ceilings, and virtually every other imaginable surface added visual complexity and spatial ambiguity in the intricately arranged, geometrically obsessive space. As one critic suggested, his approach exemplifies the counterintuitive Chinese principle that subdividing space expands it. The labyrinthine building of many levels assumes here a surreal metaphor of a utopian city.

At a time when modernism was largely about mass production, Rudolph went the opposite route, sculpturing a seemingly limitless variety of forms. Inside the trip from one room to another can take you up and down six different stairways (30).

The space stimulates a variety of experiences and feelings of exhilaration. Rudolph was a visionary, who focused on the multi sensory experience. Elevated floors forced users to slow their pace. Narrow spaces forced navigational decisions. Though the space flows in a direction, it seems infinite because its end can never be seen. Users are presented many subdivisions of pieces into small parts, which are also extended from the infinite into the infinitesimal. This continues all over the building. Special spatial experiences mixed carefully planned ambitious interiors with textured walls and a profusion of masses. Disorientation is part of this spatial intrigue, and the buildings draw the intrepid on promenades of discovery, where interior views unfold up and across the highly porous, “forest-like” plateaus. Inside, the spaces metamorphose as they flow, alternately expanding and contracting with low and high ceilings and wide and narrow passages.

Rudolph was attracted to dramatic plays of light and shadow and the highly patterned grilles emphasize the casting of reflections and shadows across the facades. According to Rohan, those effects are Rudolph’s response to the omission of decoration in the agenda of contemporary architecture. As Rohan aptly puts it:

Rudolph’s brutalism is not about the frank expression of structure and materials as described by Banham and practiced by Le Corbusier … Bearing little resemblance to Le Corbusier’s béton brut, to which it was often likened, Rudolph’s exterior surfacing, … is in fact a form of raised relief like Sullivan’s ornament (31).

Despite his ardent belief in Modernism, Rudolph was unafraid of ornament on his own terms, and he made decoration out of structure and light. Rudolph’s manner of drawing was the origin of his creative process, and his buildings were architectural craftsmanship. According to Reyner Banham, Rudolph’s building “when photographed was exactly like a drawing, with all the shading on the outside coming out as if it were ruled in with a very soft pencil” (32).

Yet, the photograph is unable to register the empirical attention to detail evident in the drawing. Rudolph excelled in producing immensely complicated, large-scale sections and perspectives. He closely supervised the process of rendering (working sketches into presentation drawings for his clients) because it was integral to his method of design. He controlled every line in every rendering. He had a signature drawing style. This was a crucial aspect of his work. For Rudolph: “The section for me is as important as the plan, maybe more important because it tells you more about the space” (33).

The muted sedate gray tones of the architect’s drawings contrast with the exciting interiors. The bridge between technology and aesthetics comes from the sense of novelty and bravura within Rudolph’s space. Scully deemed Rudolph’s Yale building “sado-masoquist.” From the prickly and bristly surface at Yale, Rudolph turned to a smoother, rippled, undulated form at the UmassD. There, it seems the form is to be touched, sensed, a part of the experience. UMassD’s relatively smooth surfaces produced by vertical forms are repeated all over the campus. In Rudolph’s design, spaces developed simultaneously with the structure; the movement is implicit in it.

UMassD exemplifies everything that is compelling in Rudolph’s architecture: the spiraling space; the cantilever (provoking the juxtaposition of forces; light and heavy structures); and the purposeful placement of architectural elements to catch the light in certain ways. It is also marked by combinations of handling scale, which Rudolph said “is for me second only to space in its importance” (34). UMassD is also a showcase of two symmetrically asymmetrical buildings, exemplifying an ingenious game of asymmetry as a method of organizing space.

III. The building, the city, and the renewal of the modern

After his European “internship,” Rudolph commented:

One can talk about architectural space, but there is no substitute for actually experiencing a building or a city, of seeing architectural space at various times of day and under all types of weather, and for seeing forms in use. With notable exceptions I was impressed much more by the great architecture of the past than by the contemporary efforts … (35)

Rudolph’s first major non-residential project was the Jewett Arts Center, a modern work inserted in the verdant landscape of Wellesley, a nineteenth-century neo-Gothic American college. This physical and intellectual setting placed the problem of modernism and history in high relief. According to Deborah Fausch, the sense of history, the understanding of the relationship of the present to the past, is highly developed in this building. Fausch points to Rudolph’s building and its relation to the campus. Accordingly, the Jewett Center is a lesson of “mannerly relationships with older neighbors” (36). Rudolph played with the relationship between the old and the new buildings by creating new “gateways” to the campus. This relationship with other buildings is seen in Rudolph’s screens, which were based on measurements made of other buildings around the Jewett Center. Another important note is the concern, in all his projects, of how lights and shadows play a part in the design. According to Fausch, the Jewett Center project suggests that for Rudolph, history is something to which modernism must be adapted, an idea that will be magnified in the complex at UMassD.

Because it was to be a commuter campus, Rudolph conceived the UMassD campus master plan after determining the location of the automobile entrance. (37) The hierarchy of buildings followed this plan. Accordingly, one of Rudolph’s guiding principles was to keep pedestrians away from automobiles; walkways were kept separate from cars and the roadway. UMassD created a vernacular that would express a specific international, modern link to other countries. In this sense, this plan expresses one version of the profoundly modern urban language of the period.

In his 1963 Yale dedication, Nikolaus Pevsner acknowledged the intelligence and beauty of Rudolph’s modern style in a bittersweet way. The old master did not feel comfortable with a lost utopian past but saw in the building an architecture suitable to its present situation, suggesting that it looked ahead to a millennial future. Pevsner equated Rudoph’s Yale building to a tweed. No better metaphor could be applied to UMassD, a campus with textile origins: Tweed expresses contradictory ideas, a rough, unfinished woolen fabric with a soft, open, flexible texture closely woven.

Rudolph’s architecture practice extended from 1952 through the early 1990s. His work ranged from his early buildings in Massachusetts to late projects in South Asia. Rudolph saw architecture as a socially committed discipline and was critical of the way modernism was institutionalized by the international style. However, by the end of the 1960s, the tables had turned. Rudolph explored mega-structures, modules, and mass-produced trailers. His projects grew increasingly larger and visionary. In the Graphic Art Project (1967) in Manhattan, he used legos to build the models.

There were setbacks at the turn of the decade and a difficult period of adaptation, when Rudolph’s projects were being canceled. In 1969, a mysterious fire nearly destroyed the Yale building and for political reasons, he left the UMassD project. The Yale building lost its identity in the renovation after the fire and the final blow came in the early 1970s with the rise of post-modernism. At Yale, the new dean, Charles Moore, opened a new era and Rudolph was targeted as representative of how things had gone wrong amid complicated house designs. The climate had changed; now, the ordinary was more relevant. Rudolph went underground for the next decade. Though post-modernism and the rise of historic preservation in the late 1970s marginalized Rudolph in the United States, (38) the early 1980s blew a second wind and he produced works in Southeast Asia, where he moved from the heavy concrete to lighter materials. (39)

When Rudolph died in 1997, he was “lauded as a homegrown talent who had adapted the idea of European modernists … into a uniquely American body of work” (40). The high quality of his work placed him at the center stage of modernism in the U.S., and the UMassD campus became an exemplary model of this architecture.

But how did his buildings fare over time? According to the year-end list of Preservation Online, 2006 was a tough year for Rudolph’s works. Anastasia Bowen reports that one of Rudolph’s Florida houses was torn down because it was “too modernist.” Though most of his works survived post-modernism, many of Paul Rudolph’s works are still in danger. Two of his vital buildings, the Orange County Government Center in Goshen, New York, and the Blue Cross/Blue Shield Building in Boston, Massachusetts, are threatened with destruction. The latter may be demolished to make way for an 80-story tower designed by Renzo Piano.

On the other hand, many of Rudolph’s works adapted to the new times. Under the new University of Massachusetts system, the campus at Dartmouth has expanded in different ways. It became a center-piece in a system that dotted the regional fabric with different schools. This new network include a new School for Marine and Science Technology (1997) located in New Bedford; the Star Store building (2001) in the heart of the city of New Bedford (including the University Art Gallery), the Advanced Technology and Manufacturing building (2001) in Fall River; the fully renovated Cherry and Webb building (2002) in Fall River; and the centrally located Center for Professional and Continuing Studies (2004) in New Bedford. The campus received two new residence buildings (2002) and, in 2004, under severe criticism, a controversial building for the College of Business was inserted into Rudolph’s master plan. (41)

Conclusion

In his 50-year-long career, Paul Rudolph’s reputation met ups and downs and his works became synonymous with the modern architectural discourse and sociopolitical moment they represented. Rudolph’s ideas matured during the debates of the 1950s, and his works were a model for a new generation. Critics today have rehabilitated Rudolph’s modernism. At UMassD Rudolph’s modernism exemplifies the brutalist style whose terms were appropriated in the service of its particular situation. Rudolph’s building, once rejected as facile, empty styling, now seems, in the light of the skilled structural decoration of much neo-modernist architecture, both intellectual and beautiful.

In a 1986 interview, Rudolph explained that any project in an architect’s life comes about circuitously. One’s professional network is also often circuitous. I was educated in a brutalist school during the late 1970s and early 1980s, but Artigas’s School of Architecture (FAUUSP), built under military dictatorship (1964-1985), draws a sharp contrast with Rudolph’s exaggerated brutalist language. Two distinguished architects express a similar language using very different vocabularies. Nonetheless, in both buildings, the brutalist language fulfills its message: What is silent becomes loud and what is void signifies density. The American building, the only significant public investment in the southeastern coast of Massachusetts since the Depression, came to symbolize a very diverse community today. (42) Both works still provoke intense reactions and perception from its users and visitors, and demand constant maintenance. They show us how the modern is read and reread in those ever-changing spaces. What the renovation of those middle-aged spaces tells us about the city, its history, and modernity today is a work-in-progress. This paper is a preliminary effort of trying to understand material and ideological transformations in the second half of the twentieth-century through the strong connections between American and Brazilian modern architecture and their influence on urban public spaces. How that modern architectural language evolved in both nations is an interesting question whose story is still to be written.

notes

1

Seminário “Construindo a cidade do século XX: uma cidade americana?”. São Paulo, FAU-USP, August 13, 2007.

2

The symposium, “Breaking New Ground: Paul Rudolph and the Architecture of the UMass Dartmouth Campus,” held on April 11, 2005, included lectures, panel discussions, a walking tour, and an exhibit of the architect’s original drawings for the campus. The symposium’s guests included Timothy Rohan, Helene Sroat, and Gratten Gill. Grattan Gill is one of a small number of Frank Lloyd Wright's students from the 1950s who still actively practices architecture. An architect from Sandwich, Mass., Gill participated in the apprentice system Wright developed at his Taliesin studios in Spring Green, Wisconsin, and Scottsdale, Arizona.

3

I would like to specially thank Allyson Cywin and Rhonda Fazio at the Visual Resource Center, Heather Tripp and D. Confar at the PhotoGraphics Department, and acquisition librarian Bruce Barnes, who organized and chaired the Rudolph Symposium in 2005. For more information see the Paul Rudolph Foundation at www.paulrudolph.org/ or search in the university library’s online catalogue at www.umassd.edu.

4

Two editions of The New York Times Magazine dealt with issues of aging and architecture: “The New Middle Ages: A Special Issue” of May 6, 2007 and the “Architecture Issue” of May 20, 2007. The New York Times Style Magazine dedicated a significant number of pages to Brazilian architecture in its “Op Culture” Design Issue of Spring 2007 and “Ahead of The Curve” Travel Issue of Spring 2007.

5

In the early twentieth-century Brazil, a modern cultural language developed by adapting the regional modernism of the Paulista elite to the “new” discourse of its emerging technical middle-class and industrial working class in the 1930s (see MEHRTENS, Cristina. “Municipal Employees and the Construction of Social Identity in São Paulo, Brazil, 1930s,” Municipal Services in the Modern City,” Ashgate, 2003; MEHRTENS, Cristina. “Politics and Urban Space: Constructing Social Identity and the Middle Class in São Paulo, Brazil, 1930s-1940s.” PhD Dissertation, University of Miami, 2000).

6

As a navy supervisor, he saw the mass production of ships at first hand and was exposed to new construction materials like plastic.

7

In 1986, Robert Bruegmann interviewed Rudolph for the Chicago Architects Oral History Project, whose goal was to produce a short catalogue displaying drawings of the Yale School of Architecture and explaining the links between Frank Lloyd Wright and Rudolph. In this interview, Rudolph acknowledges Wright’s constant influence in his handling of space and also shares humorous facts related to his first encounter with Wright in Princeton and later in Philip Johnson’s home.

8

To explore Rudolph’s motivations and the social context that influenced him in the early 1940s see Timothy Rohan (ROHAN, Timothy. “Rendering the Surface: Paul Rudolph’s Art and Architecture Building at Yale”. Grey Room 1, 2000, p. 84-107) and Christopher Dormin (DORMIN, Christopher and Joseph King (curators). “PAUL RUDOLPH: The Florida Houses” Exhibition at UMass Dartmouth with Photographs by Ezra Stoller. February 3-March 24, 2006; DORMIN, Christopher. Paul Rudolph: The Florida Houses. Princeton Architectural Press, 2002). Rudolph took the Harvard box and fit it into the sunny, beneficent climate of Sarasota, Florida. This early production became prototype of many houses he built as meditations on climate and locale. Concrete was made of local sand and his architecture adapted other local materials to give a rich warm inflection to its modern result. Dormin explains that the "early residential work...provided the necessary testing ground for Rudolph's developing multi-layered design methodology. These houses were widely published at the time of their conception and played a significant role in the culture of American design at mid-century" (Catalogue 2006).

9

Rudolph used plastic in layers (as he saw it being used in ships) to create a plastic roof in some of his residential projects.

10

In 1954 Rudolph got inspirations from traditional Caribbean shutters in a frontal critique to the international style led by Mies, Johnson, and the prevailing methods. Rudolph stressed that “we need caves as well as gold fish balls…” (ROHAN, Timothy. “Enriching Modernism: Paul Rudolph and Postwar Architecture, ” Paul Rudolph Symposium. University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. April 11, 2005).

11

An important mark in Rudolph’s career came in 1954, when he was awarded the São Paulo International Prize in Architecture (RUDOLPH, Paul. “To Enrich Our Architecture,” Journal of Architectural Education 1(13), 1958, p. 9) during the celebration of the city’s 400th anniversary. Curiously, there is almost nothing written about this Brazilian experience in the books, articles, and exhibitions about the architect. In an interesting coincidence, Paulista and brutalist-to-be Paulo Mendes da Rocha graduated in architecture in this very same year.

12

From this period is the Blue Cross - Blue Shield building in downtown Boston, and also the Tuskegee Chapel with its enormous projected roof, whose interior is vibrant and colorful. Other projects at this time resume his experimentation with concrete.

13

Historically, Massachusetts was the cradle of industrialization in the United States. The first textile factories were in Lowell. In the state southeastern coast, New Bedford was rich during the whaling industry and turned to textiles at the end of the 19th century. At the turn of the 20th century, the state legislature chartered Textile Schools both in New Bedford (1895) and Fall River (Bradford Durfee Textile School, 1899). In the 1940s, both schools changed their names to New Bedford Institute of Technology (NBIT) and Bradford Durfee Institute of Technology (BTI) to focus on a more generalized education. The latter turns into a college in 1957. Between 1963 and 1965, BTI combined with the NBTI to form the Southeastern Massachusetts Technological Institute (SMTI) located between those two cities in the town of Dartmouth. Reflecting new academic programs SMTI became Southeastern Massachusetts University (SMU) in 1969. In 1991, a new University of Massachusetts structure combined the Amherst, Boston, and Worcester campus with the Southeastern Massachusetts University at Lowell. In 1991, SMU became the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. See www.umassd.edu/about/timeline.cfm for a complete timeline of UMass Dartmouth history.

14

In a 1996 interview, Rudolph told Lasse Antonsen that, “I was commissioned by a Boston firm, Desmond & Lord, a distinguished architectural firm with direct connections to the government of the state of Massachusetts … The contractual arrangements over the thirty odd years in which I found myself working on that campus [constantly] changed … (I was) working almost sub rosa when my own fortunes in relation to the campus changed.” (ANTONSEN, Lasse B. “Interview with Paul Rudolph,” January 12, 1996)

15

ROHAN, Timothy. “Rendering...” Op. Cit..

16

The sequence of completion was as follows: academic building (Group I, 1966); science and technology building and research building (Group II, 1969); and the administration building (1970). The campus was completed in the Fall of 1971.

17Architect Grattan Gill explained that he worked at Architects Collaborative in 1963, when a mutual friend and colleague called him to join in Rudolph’s project. He liked PMR, as he referred to the architect, and so he came and secured his job as captain of the project. He went on to say that that was one of the most exciting times of his life and that in 1970 he joined PMR again (Gill’s testimony during the 2005 Symposium; GILL, Grattan. “The Master Plan: Its Design and Execution,” Paul Rudolph Symposium. University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. April 11, 2005).

18

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (1917-1963) graduated with honors from Harvard in 1940 and was politically active in Massachusetts throughout Rudolph’s formative period.

19

Rudolph would explain that, “I’ve never had an original idea. I try to understand … don’t care whether people like or dislike things, I care about whether they find anything in them that means something: it can be negative or positive” (BRUEGMANN, Robert. “Interview with Paul Rudolph,” Compiled under the auspices of the Chicago Architects Oral History Project. The Art Institute of Chicago. February 28, 1986, p. 24). He continues: “I think things grow, one thing from another, and develop, and retard and take side trips and whatnot. [International-style modernists] figured out a lot of things to give you a base to proceed” (BRUEGMANN, Robert. Op. Cit., p. 53).

20

ROHAN, Timothy. “Rendering...” Op. Cit..

21

Rohan goes on to argue that the curtain wall came to represent the corporate culture that fully embraced this language in the 1950s.

22

ROHAN, Timothy. “Rendering...” Op. Cit., p. 85.

23

Rudolph visited Le Corbusier’s béton brute (raw concrete) government building in Chandigarh and was touched by it. He also was influenced by Mies’s horizontal flowing space. See BRUEGMANN, Robert. Op. Cit., p. 22-23.

24

To achieve the desirable texture, Rudolph mixed local materials, many times selective micas, seashells, stones, and even branches of corals into the aggregate. The use of indigenous material was present during his entire career. Later, in the 1990s, in Singapore, he used bamboos for the shingles of the Wee Ee Shao residence.

25

BRUEGMANN, Robert. “Interview with Paul Rudolph,” Compiled under the auspices of the Chicago Architects Oral History Project. The Art Institute of Chicago. February 28, 1986, p. 31.

26

Timothy Rohan traced Rudolph’s development of the surface, the product of a broader investigation into methods of architectural drawing, education, and decoration, back to Louis Sullivan to make the point that in times of closeted sexuality the “brutalism” of his surfaces was a response to the possible effeminacy of ornament (see ROHAN, Timothy. “Rendering...” Op. Cit.).

27

ROHAN, Timothy. “Rendering...” Op. Cit..

28

CHASIN, Noah. “Paul Rudolph: Selected Drawings.” The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 57(3), 1998, p. 316-18.

29

ROHAN, Timothy. “Rendering...” Op. Cit., 91.

30

BERNSTEIN, Fred A. “A Road Trip Back to the Future,” The New York Times March 23, 2007.

31

ROHAN, Timothy. “Enriching...” Op. Cit..

32

Quoted by ROHAN, Timothy. “Rendering...” Op. Cit., 87.

33

BRUEGMANN, Robert. “Interview...” Op. Cit., p. 27.

34

Idem, ibidem, p. 7.

35

RUDOLPH, Paul. “Paul Rudolph,” Perspecta 1, 1952, p. 21.

36

FAUSCH, Deborah. 2001. “Rococo Modernism: The Elegance of Style,” in Resurfacing Modernism, Perspecta 32, 2001, p. 13.

37

According to Driscoll the potential users were commuter students. Arthur D. Little, Inc. of Cambridge made a demographic study to determine the potential student enrollment of the new school. The study was restricted to Massachusetts communities within 50 miles of the campus in Dartmouth, on the assumption that commuting students would travel for an hour or less to attend college. (The Standard Times May 12, 1963).

38

From the period are the Bass house in Texas (considered a Fallingwater without the water) and his own home in Manhattan, which became his experimental playground.

39

According to ROHAN, Rudolph’s career blossomed and came full circle in Southeast Asia.

40

BERNSTEIN, Fred A. “A Road...” Op. Cit..

41

Rudolph’s buildings have always had maintenance problems. Some of the flat roofs leak when it rains. But there is a pride of place; all of the screen savers in the library display the very building that contains them.

42

The importance of the recent Brazilian immigration in this area should be noted.

references

“Best and Worst of 2006. Our Year-End List of Preservation Woes and Wonder.” Preservation Online. December 29, 2006.

BOWEN, Anastasia. “Too Modernist,” Florida Inside Out. May/June, 2006.

BOWEN, Ted Smalley. “Rudolph Building, Eyed for Piano Skyscraper, Gets Temporary Stay of Execution,” Architectural Record, March 15, 2007.

“Bright New Arrival,” Time Magazine. February 1, 1960.

FISHER, Thomas. “Nietzsche in New Haven: How One Philosophizes with a Hammer,” Perspecta 29, 1998, p. 50-59.

GIOVANNINI, Joseph. “If There Is Heaven, It Should Expect Changes,” NYT, August 14, 1997.

HALL, Stephen S. “Can Science Tell us Who Grows Wiser?” The New York Times Magazine, May 6, 2007.

HAY, David. “Another Building by a Noted Modernist Comes Under Threat, This Time in Boston,” The New York Times, March 7, 2007.

IOVINE, Julie. “A Treasure at Yale, Freed of Wallboard,” The New York Times. November 16, 2000.

MCDONOUGH, Tom. “The Surface at Stake: A Postscript to Timothy M. Rohan’s ‘Rendering the Surface’” Grey Room 5, 2001, p. 102-111.

MCQUADE, Walter. “The Exploded Landscape,” Perspecta 7, 1961, p. 83-90.

MELLINS, Thomas. “An Architect’s Home Was His Modernist Castle,” NYT, June 21, 1998.

OUSTERHOUT, Robert G. “On the Destruction of Paul Rudolph’s Science Christian Building: The Vicissitudes of Functionalism,” Inland Architect 31(2), 1987, p. 66-73.

PEVSNER, Nikolaus. “Address Given at the Inauguration of the New Art and Architecture Building at Yale University, November 9, 1963,” The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 26(1), 1967, p. 4-7.

POGREBIN, Robin. “Last Exam: Renovate a Master’s Yale Shrine,” The New York Times, July 1, 2006.

RUDOLPH, Paul. “Regionalism in Architecture,” Perspecta 4, 1957, p. 12-19.

“Saving a Modern Masterpiece,” Editorial The Boston Globe, April 16, 2007.

“SMTI President Tells Hopes, Goals for the University,” Standard Times New Bedford, MA, May 12, 1963.

SROAT, Helen. “Brutalism: An Architecture of Exhilaration,” Paul Rudolph Symposium. University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, April 11, 2005.

TILLMAN, Zoe. “A New Endangered Species: Modern Architecture,” The Christian Science Monitor, June 20, 2007.

about the author

Cristina Mehrtens, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth.