Last May, San Paolo, the largest and richest city in Brazil, was paralysed by an informal curfew. For three days, buses didn’t run, schools released their students and companies closed down in the middle of the working day. A criminal organisation, the PCC (Chief Command of the Capital), had revolted against the transfer of prisoners from its clan, killing 23 policemen and spreading an atmosphere of terror throughout the metropolitan region - 18 million people - which concentrates 20% of the Brazilian GDP. The reaction of the police was not slow in coming. In clashes on the outskirts at least 122 civilians were killed, most of whom had no criminal record. The repression did not arouse any substantial protest.

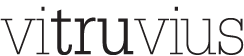

A week after the imposed curfew, the opening party for the biggest building venture in San Paolo’s recent history took place. With an architectural style that is a cross between Versailles and Las Vegas, “Parque Cidade Jardim” is a 700 million dollar complex with six residential tower blocks, five more for offices and a shopping centre. The project’s promoters sell the idea of living, working and spending one’s leisure time (i.e. going shopping) in the same ‘protected’ place. Sixty per cent of the apartments, valued at between 800,000 and 12 million dollars, were already sold during the opening.

For decades, the Panorama favela has occupied the area where Parque Cidade Jardim will stand. For the inauguration party, the entrepreneurs put up barriers to wall off Panorama. The concept of bunkers seems increasingly successful. While street commerce throughout the city suffers, 75 shopping centres prosper.

On the other side of San Paolo is Cidade Tiradentes, the largest public housing complex in the country. It was created by successive state and city administrations in an area of the Mata Atlantica forest and consists of hundreds of identical buildings surrounded by favelas. 280,000 people live there, 40 kilometres from the city centre. For the past 20 years most public housing complexes have tended to be built on the extreme outskirts. Without decent metro or public transportation, the average Cidade Tiradentes worker has to spend between two and three hours getting to work; the same getting home. Although it has existed for over 20 years, the district still has no library, cinema or bank.

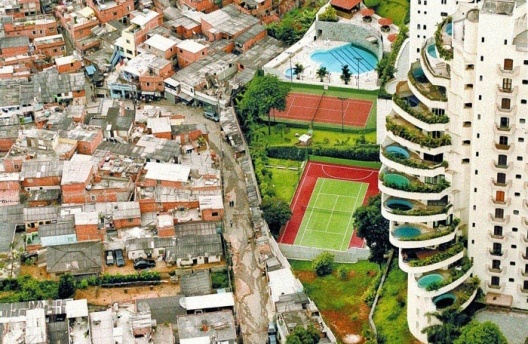

San Paolo has a surface area of 1,500 square kilometres. In 1900 it had 240,000 inhabitants. Excluding the metropolitan area, the city now has a population of almost 11 million. In 1981 there were eight million inhabitants and 1.6 million cars. Today six million cars operate on its streets and a thousand new cars are registered every day. Public transportation is growing at a much slower rate. The underground rail system, begun in 1968, extends for 60 kilometres, which is equivalent to less than a third of the system in Mexico City. There are only 26 kilometres of cycle tracks, 20 of which are in parks. But there are a good 1,000 private helicopters – the second biggest private fleet in the world.

The city centre has been experiencing a process of decline since the 1970s. Various campaigns to revitalise it have had very limited results. Major real estate companies and important business firms have fled the area. 18% of the houses are vacant and entire buildings have been empty for more than ten years. In the west and central parts of the city, which have the best public infrastructure, the number of inhabitants continues to decrease. Here there are three jobs per resident. In Cidade Tiradentes, the rate is .08 per person. The disproportionate distance between residencies and places of work results in a strain on the already overwhelmed public transportation system.

The outskirts continue to expand. About 35% of the city is environmentally protected. Some of this area is occupied by two dams which provide water to the city’s inhabitants. The zones around them are being increasingly invaded by informal settlements of wooden shacks. There are more than 1.6 million people living between the Guarapiranga and Billings dams. Clandestine connections to water and sewer compromise the quality of the water for the rest of the city. Population growth is more concentrated in the regions least provided with urban, social, leisure or employment infrastructure.

Of the municipality’s 1.500 square kilometres, 870 are urbanized, where 65% of the population resides. Illegal occupations, which account for approximately one third of the municipality’s land, are home to close to 2.5 million inhabitants. Close to 1,900,000 people live in 1855 favelas. Of this total, 65% occupy municipal terrains originally destined to become environmentally protected areas.

San Paolo is a synthesis of the world’s north-south conflicts. The best social welfare systems are in countries with low birth rates and an aging population while in countries with large young populations, there are no social welfare systems. But the richest countries build virtual or tangible barriers to keep out the poor. Being in need of cheap labour, however, they create systems that perpetuate the illegality and economic segregation of many of these people. San Paolo is already barricaded.

Anthropophagy and audacity

The city has not always been a magnet for workers. Founded in 1554 by the Jesuits, San Paolo hibernated for almost three centuries, as it was not located on the coast, nor did it have gold or precious metals. By 1822, the year of Brazil’s independence, it had only 7,000 inhabitants. In 1870 the population barely reached 30,000. Thanks to the coffee plantations that developed within the state, the city attracted millions of immigrants in search of work. And thanks to its geographical location, at the source of rivers which flow towards the inlands and the end of the plateau which leads to the port of Santos, the city accumulated a vast new wealth.

San Paolo has never been the capital. A greater supply of skilled labour for Brazil’s industrialisation was available in the city than in other regions that had only experienced forced labour. The children of immigrants were encouraged to study and be successful in the new world. The best universities in the country were established here.

San Paolo anticipated globalisation. It has mixed up Japanese, Italians, Jews, Arabs, Spaniards, Armenians, Portuguese, Blacks, Indians and Mulattoes from all over Brazil. The privileged young people who had studied overseas and discovered the European avant gardes promoted the Semana de Arte Moderna in 1922. They supported ‘anthropophagy’: devouring foreign arts and influences like the cannibalistic indigenous groups had done with the first Portuguese; but never restricting themselves to mere imitation. Villa-Lobos combined popular rhythms with cultured music. Niemeyer added the curve to modernism. The bossa nova Brazilianised jazz and tropicalism cannibalised rock. Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus were of course tropicalised in San Paolo.

The city centre and the Higienópolis district were turned into a kindergarten for young architects, many of whom were exiles from Europe at war. Some fine residential buildings are testimony to that period. Various adventurers turned their dreams into reality here. The immigrants and their descendents, like Giuseppe Martinelli, Pepe Tjurs and Artacho Jurado, built some of the tallest skyscrapers in the city. Assis Chateaubriand and Cicillo Matarazzo, the only great patrons of the arts in San Paolo, assembled the most impressive art collections in the country. Film and television studios, as well as the grand Bienal de Artes, were signs of vitality in San Paolo when the fourth centenary of its foundation was celebrated in 1954.

The industry of opportunity caused the city’s violent expansion. It would seem that excessive financial growth caused major damage, as happens to those who do not understand when to stop with the scalpel. During the military dictatorship, San Paolo allowed a viaduct more than three kilometres long, known as the ‘Minhocão’, to cut through historic avenues, emptying the beautiful residential buildings alongside them. For 70 years the car has had priority in all public and private ventures and initiatives; millions of dollars have been spent on tunnels, viaducts and expressways.

In recent years tunnels have been built in an attempt to ease the life of those living in the affluent residential areas of Jardins and Morumbi, but even these are now congested like the surface. Major city governmental projects include widening the expressways. Although the same approaches have been taken for over 40 years while traffic continues to worsen, private transportation continues to be the priority of the municipal government. On Fridays the city accumulates up to 180 kilometres of traffic in a single hour.

The flight of the rich

This process has been accompanied by the internal migration of the most affluent groups towards the western regions of the city. In the last 30 years, regions like Morumbi, Berrini, Alphaville and Vila Olimpia have attracted quality residences and offices. In the name of security, walls have been heightened and extended, cars have been armoured and suburbs are born inhospitable, without public squares, sidewalks or passers-by. An ineffective bunker: violence in the city has exploded, ignoring the high walls and private armed guards. In 1970 there were 9.7 murders per 100,000 inhabitants. In 1999 the figure had reached 35. Currently there are about 18.2, most of which occur on the outskirts.

Excellent architecture flourished in San Paolo’s golden age. The city has a legacy of buildings designed by two winners of the Pritzker prize, Paulo Mendes da Rocha and Oscar Niemeyer, the latter having designed the city’s most emblematic park (Ibirapuera) and building (Copan). The Italian Lina Bo Bardi, who created the celebrated Masp museum and the revolutionary Oficina theatre, has converted an old drum and fridge factory into one of the most vibrant sports, social and cultural centres in Brazil, the Sesc Pompéia.

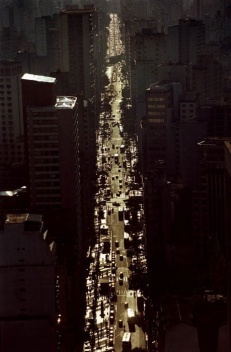

Not even all the omissions and mistakes committed have been able to contain the creative impulse of what is Brazil’s power station. Here are the country’s major industries and banks, the best universities and theatre companies, some of the leading advertising agencies in the world and an emerging fashion industry. More than 13,000 restaurants reflect the city’s cultural melting pot and worldwide power of attraction. San Paolo holds the biggest Gay Pride parade in the world which, with 2.4 million people, attests that not even waves of worldwide conservatism can bend the city’s spirit. The flight of the elite continues to segregated quarters with bucolic names: Villa this, Garden that, and so forth. This elite will spend even more time snarled up in the traffic getting to their bunker refuges. They will not use their studies abroad, their resources or ideas to find solutions for a city swamped with problems, but which can and must react. Inside their closed quarters, this elite is a long way from the best restaurants, art galleries, museums, theatres and cinemas. And unable to relish the chaos, energy and enjoyment that only a metropolis of 18 million Brazilians can offer.

note

1

Article published in BURDETT, Richard. Cities. Architecture and society. 10ª Mostra Internazionale di Architettura da Biennale di Venezia. Mestre-Venezia, Marsilio, 2006, p. 96-105.

about author

Raul Juste Lores is a Brazilian journalist. He writes in the World Affairs section of Folha de São Paulo. In 2005 he was special advisor of the Secretariat of International Affairs of São Paulo´s City Government. From 1997 to 2003, Lores wrote for Veja (weekly magazine) holding positions as editor of the World Affair section, and correspondent in Buenos Aires.