Contemporary intervention in historic and artistic architectural substance

It is not a common practice for the contemporary architect to articulate theoretical principles to fundament his design concept in buildings of architectural heritage value, be it a restoration or an intervention to adapt them to new uses and functionalities. This is even more unlikely in the case of a “star-architect”. Contrary to current trends of electing the present as the scenario of contemporaneity where the new is hegemonic in relation to history and to the history of architecture and ignoring theoretical references and ground principles of restoration, David Chipperfield (1) set a unique and inspiring precedent for the current restoration practice with the Neues Museum (1997-2009) (2) and the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin (3). In his restoration concept for the Neues Museum Berlin, Chipperfield points out that it is important “to consider the method by which we preserve our history and to what degree we destroy or confuse meaning and reality in the process of restoration or preservation” (4). If Chipperfield does not literally mention Cesare Brandi, his project, his rigid and substantial methodology and theoretical background reveal a clear conceptual and philosophical commitment to the aesthetic and historical truth, among other principles of Brandi's Teoria del Restauro (5), such as the operations of consolidation and/or reintegration of gaps, the absence of completions or stylistic remakes, the raw and untouched exposure of patina and other marks of time and human-caused events, the lack of interference in the materiality of the work of art, referring to architecture as well as, among others, murals, paintings, floors, mosaics and friezes (6).

“Desiring neither to imitate nor invalidate the remaining complex of ruined fabric [...] our concern has been motivated by the desire to protect and to repair the remains, to create a comprehensible setting, and to reconnect the parts back into an architectural whole. The project has required the construction of large missing sections of the building as well as the repair and the consolidation of the remaining parts. It has been our ambition to bind these two activities into a single approach, the new and the old reinforcing each other not in a desire for contrast but in a search for continuity” (7).

Chipperfield’s concept for the Neues Museum Berlin. The re-establishment of the building architectural potential unity

Desenho/drawings David Chipperfield Architects Berlin / Foto/photo Betânia Brendle, 2013

Chipperfield’s concept for the Neues Museum Berlin. The re-establishment of the building architectural potential unity

Desenho/drawings David Chipperfield Architects Berlin / Foto/photo Betânia Brendle, 2013

Chipperfield’s concept for the Neues Museum Berlin. The re-establishment of the building architectural potential unity

Desenho/drawings David Chipperfield Architects Berlin / Foto/photo Betânia Brendle, 2013

The restoration of the Neues Museum Berlin has the scope of its intervention restricted to the action on its material (la materia dell'opera d'arte) and the reintegration of the lost parts of the building, without imitative insertions, demonstrates, alla luce di Brandi, that the work of art is not composed of isolated parts and that even if fragmented, it still potentially exists. Carbonara defines it as "un vero restauro de natura critica e conservativa" (8).

The Neues Museum Berlin: spatial and typological re-establishment of the main staircase

Foto/photo Ute Zscharnt [Cortesia/courtesy David Chipperfield Architects Berlin]

Exceptions aside, intervention in the architecture of the past, whether ancient or Modern, is as a rule, invasive, self-referential and does not recognise its aesthetic and historical values and qualities. In many cases, it represents a constructive brutality that prioritises the supremacy of individual contemporary expression and the narcissistic freedom of fantasy that mutilates the pre-existing heritage.

These projects, mainly by architects of the international star system (sic), have in common the confrontation with the historically and aesthetically consolidated image and substance (9), and do not establish spatial and morphological dialogues with the architectural pre-existence. Rather, they are materialized "in the form of indiference, shouting, contrast and desecration" (10).

This is clearly illustrated, for example, by Mario Botta's intervention in the Church of Sant'Antonio Abate in Genestrerio, Switzerland, which shows the extent of the recurrent contemporary design arrogance and neglect for the architectural heritage denounced by Giulio Pane. A fire on 23 August 1987 destroyed a large part of the church (11), including a 18th century Baroque organ and paintings of the vault and choir. It has not been possible, in the scope of this research, to identify the nature and extent of the damage to the façade of the Church of Sant'Antonio Abate, a building integrated with the urban and architectural history of Genestrerio that still retained a spatial and morphological relationship with the place. Therefore, the annulment of the traces of the course of its history (even if reduced to a ruin) to house a brutal intervention that mutilates it and relates solely to the fantasy and narcissism of the architect Mario Botta is not justified. In Brandi's words (12):

“In that, as a work of art reduced to a ruin, it performs the function of enhancing a landscape or an urban zone, in the consciousness of a person who recognises its validity (that is, one who sees the work in this sense as active), this is connected not to its original oneness and completeness, but to its current marred state” (13).

Church of Sant'Antonio Abate, Genestrerio (Ticino, Switzerland), before the fire of 1987

Foto/photo Carlo Pedroli, 1967 [Ufficio dei Beni Culturali, Bellinzona, Switzerland]

The new facade designed by Mario Botta for the Church of Sant'Antonio Abate, Genestrerio (Ticino, Switzerland, 2003)

Foto/photo Daniela Rogantini-Temperli, 2016 [Ufficio dei Beni Culturali, Bellinzona, Suíça]

The Bundeswehr Museum of Military History, Dresden, 2011. Architect Daniel Libeskind

Foto/photo Betânia Brendle, 2015

The Elbphilarmonie Hamburg, Herzog & de Meuron, built over the Kaiserpeicher A, a listed building by Werner Kallmorgen, 1966

Foto/photo Betânia Brendle, 2017

Despite of the theoretical principles put forward by Georg Dehio (conserve, do not restore) (14) and later formulated by the the Venice Charter (15), stylistic reconstruction has been a common practice in Germany, such as those carried out, among others, in the Frauenkirche Dresden (16), Berlin Schloss e Frankfurt Dom Römer (an urban and architectural simulation that aims to reproduce the image of the city before the Second World War in the centre of Frankfurt). This wave of reconstruction means a concetual and theoretical backwards step that brings to contemporaneity the precepts of Viollet-le-Duc, in favour of the completion and stylistic remaking of a complete ideal state of fanciful visions that denature historic and artistic monuments.

The building site of the stylistic reconstruction of the Berlin Schloss

Foto/photo Betânia Brendle, 2015

The Berlin Schloss (Humboldt Forum) reconstructed

Foto/photo Betânia Brendle, 2019

These may be also illustrated by the reconstruction of the cella of the Parthenon, the object of the first complete programme of restoration in Greece, coordinated by Nikolas Balanos (1923-1933), which introduced the practices of remaking, completion and the adulteration of original constructive elements (17). Visiting the Parthenon in 1965, Cesare Brandi revealed he did not recognise the monument:

“I arrived in Athens and struggled to recognise the Parthenon. But it was a Parthenon rejuvenated, completed, and at the same time poorer” (18).

At the same time Brandi harshly disapproved the beautification operations as having a painful effect which altered the original spatial data, arguing that, "in quell che restava, il Partenone era integro e intatto" (19). He defined the desire for improvement of the Doric temple (5th century BC), as "un nostalgico desiderio del come era, dove era", which in his Theory is the antithesis of the very principle of restoration (20). Carbonara, in his technical report of 1989 took a definite stand against the anastylosis proposals for the Parthenon:

“What seems unacceptable, however, is the choice to dismantle even the original undisturbed parts, either to remove the ancient iron brackets, or even to dismantle the original sculpted pieces to be placed in the museum and replace them with copies” (21).

Restoration, when undertaken as an imitation, forgery or copy of something that no longer exists, removes the symbolic content of the building or ruin, compromising the historical and aesthetic truths that integrate a chain of values (artistic, documentary, memorial, identity, symbolic, affective, among others), that should be considered and weighed in the project. Bringing back to the present time buildings that no longer exist (except in our memory), is also a design attitude widely used in interventions in icons of Modern Architecture to simulate a bizarre return of hollow images of an idealised time forever lost. A design attitude that does not consider that time cannot return by erasing the marks (patina) left by its course that give character and authenticity and that bears witness to the functional, aesthetic, constructive, technical and technological processes of a more recent past. The brutal destruction of the remaining architectural substance and its spatiality and the indiscriminate replacement of its constructive elements nullify the documental value of the work and alter its aesthetic, spatial and tectonic code at the cost of a pretended restoration of the image (22). With rare exceptions (for example, the restoration of the Pirelli Building, Gio Ponti and Pier Luigi Nervi, Milan) (23), the restoration (sic) practices adopted nowadays, as illustrated, among many others, by the intervention in the Zonnestraal Sanatorium (24) (Jan Duiker and Bernard Bijvoet, 1931) and the Barcelona Pavilion (German Pavilion for the 1929 International Exposition in Barcelona, Spain, designed by Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich), aim at bringing back the ruins of the masterpieces of the Modern Movement to their lost ideal and conceptual state through the making of accurate copies or forgeries with claims of pretense authenticity.

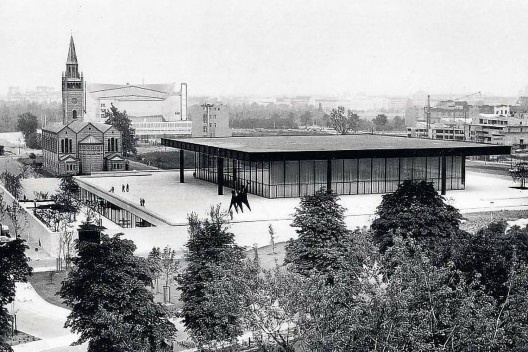

The Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin: Mies's last built work

The Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin was Mies van der Rohe's last project. “The final work in a career that continually employed geometry to master evolving technologies” (25). He was specially invited by the Berlin Senate, through Rolf Schwedler, to ensure the realisation of the “representative late work by one of the most important architects of the twentieth century” (26). In an open letter to the architect published in March 1961, Schwedler, the Senator for Building and Housing in Berlin, made public his great interest and desire to have a Mies architectural work in (West) Berlin. Mies responds positively: “But also especially for expressing once again the wish to see a building of mine in Berlin. I also would welcome such an opportunity” (27). At the same time, the Chief-Editor of Bauwelt, Ulrich Conrad (28), published a front-page story — Mies van der Rohe muß in Berlin bauen! (29), and declared “That Mies van der Rohe builds again in Berlin is our wish for him and for us on his 75th birthday”. In addition to such a distinguished official invitation and without having to submit himself, like Hans Scharoun did, to a public competition, he had the privilege to choose an area in the Kulturforum, a post-war new cultural quarter alongside the Berlin Wall, between Potsdamerplatz and Tiergarten, greatly destroyed both by demolition for the implementation of Albert Speer and Hitler's project for Welthauptstadt Germania and by intense Allied bombing.

Mies decided on a Gallery to house the collection of 19th and 20th century Prussian art and returned to Berlin for the first time since his emigration to the USA in April 1938. He was very excited at the prospect of building such an important building as part of the Kulturforum in Berlin, the city that had inspired him artistically (30). The presence of Mies van der Rohe in this desolate area of West Berlin, deeply scarred by the wounds perpetrated by the criminal nazi regime of the Third Reich and the National Socialist German Workers' Party — NSDAP, which prevented him and many other architects (among others, those of Jewish origin such as Mendelsohn and Breuer, as well as Gropius, Moholy-Nagy and Hilbersheimer) from practising Modern Architecture, forcing him to leave Germany, is highly symbolic and significant. The Berlin Senate's homage to Mies formalizes the recognition of the value and importance of one of the great Masters of Modern Architecture of the 20th Century, who, alongside with Hans Scharoun and his equally iconic Philarmonie and Staatsbibliotek, as acknowledged by masters of the late Modern, marked a new era in the post-war reconstruction of West Germany. Mies chooses a plot of land near the St Matthäis-Church with enough slope to allow the project to be structured in two levels: the ground floor, destined for temporary exhibitions of a non-traditional scope, whose conceptualization must consider the scale and specificity of the space, and the basement, which houses permanent collections. Mies was aware of the spatial individuality of the ground floor exhibition hall, criticised as unsuitable space. He saw what nobody had hitherto glimpsed: the various possibilities for artistic exploration, especially for monumental art (31). In Mies words:

“It is a large hall, which naturally means great difficulties for the exhibition of art. Of course, I am fully aware of that. But it has such great possibilities that I cannot take these difficulties into account at all” (32).

As Mies's daughter, Georgia van der Rohe, visited the Neue Nationalgalerie in the 1970s for the shooting of her film Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, she wrote:

“In the New National Gallery, my father's last building, a flying body by Panamarenko (33) had just been set up. A stroke of luck. It filled the huge exhibition space and at night, brightly lit, shone through the glass facades like a fairy tale (34).

Panamarenko's exhibition at the Neue Nationalgalerie

Foto/photo Ensembles

Basement floor of the Neue Nationalgalerie with the permanent art collection

Foto/photo Bauwelt, n. 38, 1968

The design of the Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin is part of Mies's building typology of large, square-plan pavilions, which first appeared in sketches for the 50 x 50 House (1950-1951), consisting of a deep flat roof, supported on each side by no more than two columns, which is the base of the building structure (35) alongside with its monumental free and flowing space. The fully glazed hall measures 50.40m x 50,40m and is 8.40m high. The roof has a side length of 64.8m and is the largest rigid slab ever built. The right-angled, 1.80-metre-high solid steel beams are spaced 3.60m apart (36). The integrity of the space and of the square floor plan is accentuated by its scale and rigid symmetry organized by a central axis where just a few essential functional elements are allowed such as the two large green marble-clad service stacks which houses the heating and ventilation system, the ticket booth and two wood-lined cloakrooms and staircases leading below. On the floor below are placed, besides the permanent collection, the administrative offices, a Café, an internal foyer between the stairs, a bookstore, as well as the technical, administrative and service facilities. The slope of the land made it possible to create a walled Sculpture Garden connected to the galleries by floor-to-ceiling glass panels.

“Constructed entirely of poured-in-place concrete, the lower level of the New National Galery provided a plinth not only for the glass pavilion but for a podium [...]. Like the scheme for Bacardi, it was more of an acropolis, where space and views extended to the horizon on all sides” (37).

The Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin: original ground floor plan from Mies van der Rohe

Foto/photo Bauwelt, n. 38, 1968

The Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin: original basement floor plan from Mies van der Rohe

Foto/photo Bauwelt, n. 38, 1968

The Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin had as prototypes the Ron Bacardi Administrative Building (Santiago de Cuba) and the Georg Schäfer Museum (Schweinfurt, Germany), both of which were never constructed. Schulze argues that “Berlin's National Gallery is a steel version of the Bacardi Building” (38), whose steel variant was not accepted by Schäfer, who refused to house his 19th-century art collection in such a modern steel skeleton construction. Both projects are geometric figures that express a recurrent structural logic that is apparently simple but above all pure, clear and visible. For Mies, architecture is also structure and should express the spirit of the times through contemporary materials, which in the Neue Nationalgalerie will be expressed in steel, bronze, glass, marble and granite. For these projects Mies further developed the concept of “universal space”, a spatial typology capable of housing a wide variety of activities, uses and functions, first applied in the Crown Hall (IIT Campus, 1950-1956) and in the project of the Convention Hall, Chicago (1953-1954, not built). As Spaeth (39) states, a “universal space” approaching the Convention Hall in its dimensions was not realised until the completion the Neue Nationalgalerie (1962-1968). According to Frampton (40), the steel-framed pavilion that dominates the Neue Nationalgalerie basement represents Mies's final homecoming in many respects, as he managed to put together the modern concept of space and his tectonic constructive logic, also achieving an architectural integration of two primary components of the western architectural tradition: constructive rationalism and romantic classicism.

“While the roof as a whole can be interpreted as an endless floating surface, the obvious structural substance ensures its tectonic presence” (41).

Mies's design for the Neue Nationalgalerie confers a high degree of abstraction on its external image and displays intrinsic qualities of late Modernism not only in its spatial, structural and tectonic substance, but also in the design elements strongly imbued with the spirit and individuality of the 1960s. For example, the semi-transparent curtains on the upper floor designed by Mies for functional reasons, 1. for protection against glare and sunlight and for UV reduction; 2. for forming a climate buffer for the glass façades; and 3. for minimising the reflection of artificial light at night. In 1966, Mies strongly defended the importance of the curtains in the glazed hall as an inseparable element of his project, warning, in direct correspondence with Stephan Waetzold, the Director of the Staatlichen Museen Berlin, that it must not, under any circumstances, compromise the building's legibility or purity. To the functional reasons, he adds clear and equally important aesthetic intentions.

“I have not given up the idea of the curtain. A carefully chosen curtain would not only solve the sunshade problem, but also pleasantly enrich the architectural appearance of the large hall. Whatever sun protection we provide here, it must not compromise the clarity of the building and must always be an independent addition to it” (42).

Besides the curtains, other elements of Mies's design are linked to the 1960s, such as the modular ceilings, the exhibition lighting with downlights, the wallpaper, the carpeted floor of the basement exhibition rooms and the Floor-Flex floor of the restricted public access areas (43). These elements are part of Mies's original project and confer historic and artistic value to the Neue Nationalgalerie, a building that has been listed in the Denkmalliste des Landes Berlin as a Baudenkmal or architectural monument since 1996, under the number 09050310. In 1965 Mies came to Berlin for the Grundsteinlegung (laying of the foundation stone) of the Neue Nationalgalerie. He would come once more to Berlin on 5 April 1967, at the age of 82 and in failing health, to witness in situ the lifting by hydraulic jacks of the enormous steel roof in a single piece weighing 1250 tonnes. He followed everything with great interest accompanied by his grandson, architect Dirk Lohan, the building site manager and said:

“It was agreed that nobody would speak more than five minutes. What swindled that was! I want to thank the men who worked the steel, and the ones who did the concrete. And when the great roof raised itself up without a sound, I was amazed!" (44).

This would be Mies's last visit to Berlin. His health deteriorated rapidly and he was unable to attend the inauguration of the Neue Nationalgalerie in 1968, celebrated by the New York Times as the most important work by one of the greatest architects of the 20th century.

Mies van der Rohe at the laying of the foundation stone of the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin

Foto/photo David Chipperfield Architects Berlin, 1965

As his daughter, Georgia van der Rohe reported, Mies was eagerly awaiting news of the inauguration:

“From nine o'clock in the morning Chicago time, my father was expecting a telephone report about the opening. So, at four in the afternoon, I went to the hotel and called him. Of course, he was up early with excitement and tension. He was pleased about the great approval of the Berliners, which was especially directed at him, the architect” (45).

Mies van der Rohe

Foto/photo Bauwelt, n. 38, 1968

Without ever having seen his latest work, which housed Alexander Calder's sculpture Têtes et Queue on the terrace, and an inaugural retrospective exhibition of Piet Mondrian, Mies van der Rohe died in early summer 1969 in Chicago. "He was the most abstracting architect of the century" (46).

In 2014 the Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin was closed due to severe damage of a technical nature, such as failure of the suspended ceiling, frequent breakage of glass panels in the façades, broken pipes, concrete defects, corrosion, inadequate security and fire system, insufficient technological infrastructure, for example in the ground floor heating system, among others. After more than four decades with the same use, the building aged naturally and the patina and marks of time became visible. However, the recognition of Mies's work as a listed monument, as well as one of the greatest icons of twentieth-century architecture, inhibited and restrained large-scale architectural interventions with "design ambition", being restricted to preventative measures and technical and functional maintenance of the building. This made it possible to preserve the essence of Mies's project, which reaches the 21th century without significant compromising alterations in its potential unity as a work of art.

The Neue Nationalgalerie closed (Zu) at the beginning of its restoration, with the bronze sculpture The Archer, by Henry Moore

Foto/photo Betânia Brendle, 2015

The restoration of Mies's Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin: theoretical principles and project

“The task of restoring the New National Gallery is one that concerns the skin and bones of Mies’s extraordinary building. But even this cannot be regarded from the dispassionate distance of technical solutions. Our task is not only to repair its body but to protect its soul” (47).

Restoration as a scientific discipline requires the adoption of its own theoretical principles for the conceptualization and formulation of the project. Far from being empirical and of personal taste, these principles were established throughout the construction of the modern restoration theory, initiated by the irreconcilable debate of extremely antagonistic and/or dialectical positions of stylistic restoration (Viollet-le-Duc) and of the idealizing anti-restoration (John Ruskin). These principles were pondered by Camillo Boito, who preceded and solidified the development of the modern theoretical formulations that will be proposed by Cesare Brandi in his Teoria del Restauro (48). These came to contemporaneity and were crystallized in the form of the Restauro Critico e Conservativo, which has in Giovanni Carbonara (49) its greatest exponent. Restoring deteriorated or ruined buildings imbued with heritage values through a methodological procedure that indicates the need for contemporary insertions does not mean ignoring its spatial atmosphere and the constructive and poetic dimension of elements from the past. The restoration project is an architectural project based on the understanding of the history, meaning and values of the building, by the revelations that archaeology may unveil, by the respect for the patina and the marks of the course of time and by the adoption of valid theoretical principles that support the construction of an intervention proposal.

Giovanni Carbonara argues that “the work of art is born in the artist's consciousness", and referring to Benedetto Croce, he adds that this work generated in the artist's mind is expressed in various physical materials. "The work of art is a pure and incorruptible reality", quite distinct from materiality which naturally deteriorates through the course of time or historical events (50). Thus, the restoration of the matter (materia) of the work of art should not interfere with the mental representation conceived by the artist. Any interpretative action of recomposing the lost image through subjectivity, which is a kind of fantasy, constitutes according to Brandi "the most serious heresy of restoration” (51).

The Neue Nationalgalerie, as "opera d'arte" and as one of the greatest icons of the Modern Architecture of the second half of the 20th century, has, according to Brandi, the scope of its intervention restricted to its physical materiality. Moreover, its restoration also aims at reconstituting the authentic text of Mies' architecture through the reinstallation of the potential unity of the work of art, broken by some invasive and disrespectful interventions that disregarded his original design, both spatially and tectonically.

As established by the AG-Bau Beschlussvorlage zur Gesamtsanierung der Neuen Nationalgalerie Berlin (52), due to the high heritage value of the building and its extraordinary cultural-historical significance as an icon of Modernism, changes to the building structure in terms of its dimensions or a redesign of the spatial structure were to be ruled out. It is relevant to consider that the use of the building as a Museum and/or Exhibition Hall is acknowledged as one of its most important heritage values. As the Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin was built, it was one of the first high-tech museums in Germany, equipped with an in-depth designed technical infrastructure adequate to the needs of the second half of the 20th century.

“The process of equal voting took place under our moderation between the National Museums in Berlin as users, the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation as the client, the Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning — BBR as the client's construction representative, the Berlin State Monuments Office, the State Monuments Council and the specialist planners involved, and was accompanied in an advisory capacity by the former project manager Dirk Lohan (grandson of Mies van der Rohe) and the Mies expert Prof. Dr. Fritz Neumeyer” (53).

After almost fifty years, the focus of the restoration project, as Martin Reichert reveals, "was therefore on the conflict of objectives between the needs of the use and those of the physical architectural monument" (54). To better understand the Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin´s construction and maintenance problems, an inspection of several Mies's buildings in Canada and in the USA carried out by Chipperfield's team, identified the following recurring problems: sealing, imperfect waterproofing, defective joints in terraces and flat roofs, condensation, corrosion and leakage in glass and steel façades. Particularly in the United States, the conservation approach to Modern Architecture, rather than favouring careful maintenance and repair procedures, is imbued with a thorough remaking of the buildings's physical structure with a strong impact on their external image. It has been established that the restoration of Modern Architecture outside Italy is primarily aimed at resolving technical issues and reconstructing the building's original image or reproposing its external appearance, i.e. the interventions are carried out as real re-making or repristinazione (55).

For the restoration concept of the Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin, David Chipperfield adopted early principles of restoration formulated by Adolphe Napoleón Didron: “better to repair than

to restore, better to restore than to rebuild” (56). Didron was also among those objecting the completion of destroyed parts of the Reims Cathedral in 1851:

“Just as no poet would want to undertake the completion of the unfinished verses of the Aeneid, no painter would complete a picture of Raphael’s, no sculptor would finish one of Michelangelo’s works, so no reasonable architect can consent to the completion of the cathedral” (57).

Likewise, Chipperfield refused to leave his mark on Mies van der Rohe's work. Because of the great respect for Mies' work, the project avoided, as far as possible, making visible and designed interventions and it was oriented towards the preservation of the pre-existing architectural substance. "Interventions and changes should always be limited to the minimum necessary" (58).

“In real terms our work does not require us to make any radical intrusion or alteration, but to address the relatively modest but still complicated issues that arise from the fabric of the building, and to reinstate the integrity of its structure” (59).

By drawing up the status quo of the Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin, Chipperfield's team identified a number of misused areas and areas with multiple uses, as well as the lack of space for the preparation of exhibitions, the shortcomings in the transport routes for the art and the too restricted Back-of-House areas, such as the workshop and storage areas. Besides the under dimensioned visitor services such as the cloakroom and ticket counter, the Museum Shop built in 1979, in the foyer or Trepenhalle, which greatly disrupted Mies' pure and symmetrical spatiality, was relocated. Glass panels installed near one of the free-standing staircases to improvise a shop for the Museum, compromising an extremely important component of the architectural concept conceived by Mies. This shop is seen in Brandi's Theory, as a “corpo estraneo”, inappropriately inserted compromising the architectural and spatial concept conceived by Mies (60). The restructuring of uses made it possible to re-establish Mies van der Rohe’s original layout for the public areas of the basement floor, and even without any reference to Theory of Restoration of Cesare Brandi, its theoretical principles are recognisable.

“It is clear that if the addition disturbs, perverts, obscures or detracts in part from sight of the work of art, the addition must be removed” (61).

The Museum Shop built in 1979. On the background, one of the stairs leading to the Glass Hall

Foto/photo courtesy David Chipperfield Architects Berlin

Furthermore, by removing the interim cloakroom from the northern museum corridor and the Museum Shop from the foyer, Mies van der Rohe’s original plan was restored according to the project principles and concept presented by David Chipperfield in the "Mies und das Museum Conference" held in 2014, before the restoration work began.

“We must consider the original intentions of the architect; inherent defects in the design; the issue of weathering and damage; modifications in programme and use; and the status of any changes and alterations made to the original design” (62).

The foyer (Treppenhalle) on the basement floor as Mies conceived it

Foto/photo courtesy David Chipperfield Architects Berlin

Restructuring of uses in the basement floor: the liberation of the northern Museum corridor; the new cloakroom; clearing of the foyer from the invasive insertion of a museum shop in Mies' project in 1979; and the new museum shop

Foto/photo courtesy David Chipperfield Architects Berlin

The restoration of the space designed by Mies for the Treppenhalle in the basement and the new location of the museum shop

Foto/photo Betânia Brendle, nov. 2021

As the cloakroom and Museum shop were relocated into the existing painting and sculpture depots, those had to be housed in a new subterranean building extension below the raised podium. In fact, any construction outside the boundaries of the original Neue Nationalgalerie perimeter (even underground) would be in contradiction to the resolutions set out in the project contract. However, as Reichert reveals:

“We were able to convince the AG Bau-Gremium with two arguments: firstly, the underground extensions are not perceptible either from the outside or from the public areas inside; secondly, the autonomy and existence of all functional areas of a museum represent a monumental value in their own right, which should not be relativised by the relocation of depots” (63).

The reinstallation of Mies' design on the public areas of the basement floor and the new depot and storage spaces located outside of the original perimeter of the Neue Nationalgalerie

Foto/photo courtesy David Chipperfield Architects Berlin

As established before, the defining principle of the restoration of the Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin was to reduce visible design interventions to the minimum and to preserve and/or restore the substance and essential architectural thoughts of Mies van der Rohe. In order to re-establish Mies's spatial conception and design for the basement floor, it was essential to remove an addition that had functioned since 1979 as an improvised book shop as well as the interim visitor´s cloakroom installed in the museum's north corridor and to house them in new storage areas for paintings and sculptures. For Martin Reichert, “the two depots would be noticeably converted, but not redesigned” (64). The legibility of the former storage areas should be guaranteed, so that visitors would notice at first glance that this space was not originally open to the public. Therefore, the project to convert the two deposits and storerooms into a cloakroom and museum shop completely distanced itself from the mimetic reproduction of Mies's design principles used for the public areas of the exhibition halls. These would cover the modular exposed concrete ceiling, the walls and the mushroom slab concrete columns that support the steel structural system of the glazed hall on the upper floor. Instead, the design intervention is clearly aimed at preserving the tectonic truth that still exists in the materials and structural elements.

The paint depot before its conversion into a visitors’cloakroom

Foto/photo Betânia Brendle, 2020

The new visitors’cloakroom (Garderobe) in April 2021

Foto/photo courtesy David Chipperfield Architects Berlin

The new Museum Shop (Museumsshop) in April 2021

Foto/photo courtesy David Chipperfield Architects Berlin

This intervention is not invisible. It is not only undeniably perceptible, but bold, courageous and clearly reveals the presence and untouchability of the structural system and the materials of the walls and floors designed by Mies. A contemporary manifesto against ambiguous analogical integrations, opposed to architectural authenticity and design truth. As Cesare Brandi argues:

“The two moments in the history of art will always remain separate, as will the historicity of the work of art (as created by the artist), from the historicity it enjoys once it enters into the world of life” (65).

"Less is More"

Mies van der Rohe had his last architectural work preserved by the attentive and conscientious restoration of David Chipperfield, who adopted, as the defining criterion of the project, the recognition of the heritage value and cultural, artistic and historical significance of the Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin as a unique and non-reproducible Monument. By defining the preservation of "Mies's soul" as the determining conceptual axis of his project, Chipperfield established the following theoretical principles to guide the restoration of the Neue Nationalgalerie: the minimum intervention, the integral preservation of the pre-existing architectural substance (spatial and tectonic), the refusal to carry out analogical remaking and the not invasive distinguibility and legibility of contemporary interventions.

By assuming as elements of the restoration project, the natural aging of the Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin and the construction deficiencies and deterioration that occurred in its physical structure over time, he ensured respect for the history of the building and refused the recurrent application of the "principio del com'era e dov'era". The greatest challenge was to reconcile the great respect and desire to preserve this icon of Modern Architecture to pass it on to future generations with its suitability to the operating standards of a contemporary museum. Technical and functional aspects of the restoration were thoroughly examined (66), among others, the issues of high condensation and constant breaking of the glazed hall windows, fire safety and the promotion of accessibility, a requirement that did not exist at the time the building was built.

The restored Mies van der Rohe's Neue Nationalgalerie, April 2021

Foto/photo courtesy David Chipperfield Architects Berlin

The restored facade of the Neue Nationalgalerie with the reinstallation of the curtains designed by Mies

Foto/photo Betânia Brendle, nov. 2021

The Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin, Mies van der Rohe's last built work, reopens to the public with Alexander Calder's exhibition, Minimal / Maximal

Foto/photo Betânia Brendle, nov. 2021

The Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin, Mies van der Rohe's last built work, reopens to the public with Alexander Calder's exhibition, Minimal / Maximal

Foto/photo Betânia Brendle, nov. 2021

The Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin, Mies van der Rohe's last built work, reopens to the public with Alexander Calder's exhibition, Minimal / Maximal

Foto/photo Betânia Brendle, nov. 2021

In the restoration of the Neue Nationalgalerie, the recurrent action of many contemporary architects and their arrogant and brutal design that denaturalises, offends and destroys the heritage of the past (ancient or Modern) is not visible. Nor is visible, the practice of stylistic forgeries and remakes and/or aggressive and inconsequential additions that transform pre-existing built heritage into a backdrop for the physical expression of the present, the only time that counts. By establishing "invisibility" as the Leitmotiv of his restoration project, Chipperfield gave high priority to the hegemonic preservation of the Miesian legacy through design attitudes directed towards the restoration of "Mies's soul" expressed in architecture through high abstraction, universal space, light, and structural and tectonic truth... when “l'immagine è la material”.

“Our team at David Chipperfield Architects regarded ourselves as "invisible architects", who planned and implemented the required adaptations and measures in the service of and with a responsibility toward the original designer, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, thereby refraining from incorporating our own personal preferences” (67).

This respectful attitude of the restoration project of the last architectural work built by Mies will never be invisible; on the contrary, it will be an inspiration for contemporary and future generations of thousands of young architects who, touched by the "invisible architect", may awaken to the importance of preserving the work, thought and architectural visions of the great Masters of the Modern Movement.

“Thus, one restores in architecture by doing architecture […]. Architecture and restoration design, or rather, 'in the service of restoration' of cultural heritage, i.e. a way of designing strongly guided by a solid historical awareness and attention” (68).

The restored glazed hall of the Neue Nationalgalerie, April 2021

Foto/photo courtesy David Chipperfield Architects Berlin

The restored Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin is open to the public with the sculptures The Archer, by Henry Moore and Têtes et Queue by Alexander Calder and the oil painting by Tarsila do Amaral, Distance, 1928, from the exhibition — Art in Society 1900-1945

Foto/photo Betânia Brendle, nov. 2021

The restored Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin is open to the public with the sculptures The Archer, by Henry Moore and Têtes et Queue by Alexander Calder and the oil painting by Tarsila do Amaral, Distance, 1928, from the exhibition — Art in Society 1900-1945

Foto/photo Betânia Brendle, nov. 2021

notes

NA — With special thanks to Martin Reichert (Director and Partner, David Chipperfield Architects Berlin) and to professor Giovanni Carbonara (Università di Roma "La Sapienza"). And also to Carolina Chaves (Instituto Superior Técnico-Universidade de Lisboa/Universidade Federal de Sergipe), Rubens Luiz Santos and Fábio Araújo. The translation of the German, Italian and Portuguese texts was carried out by the author.

1

Named Commander of the Order of the British Empire — CBE in 2004 for services to architecture, internationally acclaimed and holder of several prestigious architectural awards, such as the 2011 European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture — Mies van der Rohe Award, for the restoration of the Neues Museum in Berlin, carried out in conjunction with Julian Harrap, London.

2

BRENDLE, Betânia. O projeto de restauração e intervenção como projeto de arquitetura: Cesare Brandi e o Neues Museum Berlin. Conference Proceedings of the VI Projetar, Salvador, 2013.

3

As Jury Chair Mostafavi states: “The rebuilding of the Neues Museum Berlin is an extraordinary achievement. Rarely have an architect and client succeeded in undertaking a work of such historic importance and complexity; especially one that involves both preservation and new building”. Minner, Kelly. David Chipperfield's Neues Museum Receives 2011 Mies van der Rohe Award. ArchDaily, April 11, 2011 <https://bit.ly/3HlgPhv>.

4

CHIPPERFIELD, David. The Neues Museum Architectural Concept. The Neues Museum Berlin. Conserving, restoring, rebuilding within the World Heritage, Leipzig, E.A. Seemann, 2009, p. 55.

5

BRANDI, Cesare. Teoria del Restauro, Roma, Edizione di Storia e Letteratura, 1963. In this article it will be used the english edition of the Theory of Restoration. BRANDI, Cesare. Theory of Restoration. Roma, Istituto Centrale per il Restauro/Nardini Editore, 2005.

6

BRENDLE, Betânia. Cesare Brandis Theorie der Restaurierung in der Architektur: das Neue Museum Berlin. Post-Doctoral Research. Dresden, Technische Universität Dresden, Institut für Baugeschichte, Architekturtheorie und Denkmalpflege, 2015.

7

CHIPPERFIELD, David. Op. cit., p. 56.

8

CARBONARA, Giovanni. Architettura d'oggi e restauro. Un confronto antico-nuovo, Torino, UTET Scienze Tecniche, 2013, p. 124.

9

Among others: 1. the new facade for the Church of Sant'Antonio Abate, Genestrerio (Ticino, Switzerland), Mario Botta (1999-2003); 2. Militärhistorisches Museum der Bundeswehr, Dresden, Daniel Libeskind; 3. Elbphilarmonie Hamburg, Herzog & de Meuron, built over the Kaiserpeicher A (project of Werner Kallmorgen, 1966); 4. Ginger & Fred (sic), Prage, Frank Gehry; 5. Ara Pacis, Roma, Richard Meier; 6. Lione's Opera House, Jean Nouvel; 7. Kunstmuseum Moritzburg, Halle, Alemanha, Nieto Sobejano Arquitectos.

10

PANE, Giulio. Storia e metaprogetto nell'Incontro tra antico e nuovo. Atti del Convegno Antico e Nuovo: Architetture e architettura, Venezia, 2007, p. 70.

11

Probably built in the 15th century, the Church of Sant'Antonio Abate in Genestrerio, undergone various changes throughout the centuries with additions in Baroque taste and in Neoclassical language.

12

BRANDI, Cesare. Op. cit., p. 72.

13

In the original edition of Teoria del Restauro, Brandi used the word mutilazione, which in English is also translated as mutilation. BRANDI, Cesare. Teoria del Restauro (op. cit.), p. 70.

14

"Was wird aus dem Heidelberger Schloß werden?" (What will become of the Heildelberg Castle?), Georg Dehio's thesis formulated in 1901 against its reconstruction anticipating fundamental precepts for the conservation of monuments in Germany that would later be critically and scientifically developed by Cesare Brandi in his Theory of Restoration (1963) and incorporated in the Venice Charter (1964). In BRENDLE, Betânia. Konservierung, nicht Restaurierung: Georg Dehio e as raízes da moderna Teoria de Restauração. Conference Proceedings of — De Viollet-le-Duc à Carta de Veneza. Teoria e prática do restauro no espaço ibero-americano. Lisboa, Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil/Instituto de História da Arte da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa, 2014.

15

International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites — A basic document adopted in 1965 by Icomos, a non-governmental international organisation dedicated to the conservation of the world's monuments and sites. The Venice Charter resulted from the II International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments, held in Venice from 25 to 31 May 1964. See KÜHL, Beatriz Mugayar. Notas sobre a Carta de Veneza. Anais do Museu Paulista: História e Cultura Material, v. 18 (n. 2), São Paulo, 2010, p.287-320.

16

BRENDLE, Betânia. Frauenkirche Dresden. Reconstrução ou Montagem Cênica? Revista Continente Multicultural, n. 74, Recife, 2007, p. 50-55.

17

“E la stessa mancanza di rispetto per il materiale antico la si trova negli innumerevoli fori aperti o nella quantità di materiale estratto dagli elementi architettonici antichi per inserire in essi nuove grappe o intere armature in ferro”. MALLOUCHOU-TUFANO, Fani. Interventi di restauro sull’Acropoli di Atene dal 1975 ad oggi. In CASANAKI, Maria, MALLOUCHOU, Fani. The Acropolis at Athens: conservation, restoration and research 1975-1983. Exhibition Athens. The National Gallery Alexandros Soutzos Museum, 1985, p. 207.

18

“Sono arrivato ad Atene e stentavo riconescere il Partenone. Ma era un Partenone ringiovanito, completato, e al tempo stesso più povero”. BRANDI, Cesare. La ricostruzione del lato nord del Partenone. In CORDARO, Michele (ed.). Il Restauro. Teoria e Pratica. 1939-1986. Roma, 1994, p. 166. Originally published as: BRANDI, Cesare. Il Partenone non è più il Partenone dopo le ricostruzioni ‘storiche’. Il Corriere della Sera, 14 giugno 1965.

19

BRANDI, Cesare. La ricostruzione del lato nord del Partenone. In CORDARO, Michele (ed.). Op. cit., p. 167.

20

“The nostalgic saying, 'as it was, where it was', is the negation of the very principle of restoration. It is an offence against history and an outrage to aesthetics, claiming that time can be reversed, and that a work of art can be reproduced at will”. BRANDI, Cesare. Op. cit., p. 75.

21

“Ciò che appare comunque inaccettabile è la scelta di smantellare anche le parti originali indisturbate, o per rimuovere le antiche grappe di ferro, o anche per smontare i pezzi scolpiti originali da collocare in museo e sostituire con copie”. CARBONARA, Giovanni. Answers concerning the anastylosis proposals. 3rd International Meeting for the Restoration of the Acropolis Monuments, Athens, 31 March/2 April 1989. Proceedings, Athens 1990. Appendice II, s.p. [ma pp. 303-308].

22

“O princípio superado da restauração da imagem e não da matéria e rejeitado por Cesare Brandi em sua Teoria del Restauro, tem constituído o eixo condutor da reconstrução fiel e exata da Arquitetura Moderna, que via de regra, não admite a falta da integridade física e da perfeição, afastando-se do campo teórico e dos preceitos do restauro para reviver o edifício mesmo através de uma cópia, réplica ou simulacro”. BRENDLE, Betânia. Uma incompleta e vaga lembrança: a reconstrução “evocativa” das residências dos Mestres da Bauhaus em Dessau. Conference Proceedings of the XI Seminário Nacional do Docomomo Brasil, Recife, UFPE, 2016.

23

CARBONARA, Giovanni. Il restauro fra conservazione e modificazione. Principi e problemi attuali. Roma, Artstudiopaparo, 2017, p. 35-36. "Quando, superate le prime posizioni a favore uno spinto rinnovamento, formale e tecnologico, delle superfici in curtain-wall si è, al contrario, intrapeso um lavoro di conservazione e riparazione".

24

MEURS, Paul, THOOR, Marie-Thérèse (ed.). Zonnestraal Sanatorium: The history and restoration of a modern monument. Rotterdam. NAi Publishers, Zonnestraal Estate by MIT, Faculty of Architecture, TU Delft, 2010.

25

MERTINS, Detlef. Mies. London, Phaidon, 2014.

26

HAFTMANN, Werner. Von den Traditionen und vom Stand der Neuen Nationalgalerie. Jahrbuch Preussischer Kulturbesitz, n. 5, Berlin, 1967, p. 177.

27

“Aber auch besonders dafuer, daß Sie erneut dem Wunsch zum Ausdruck bringen, einen Bau von mir in Berlin zu sehen. Auch ich wuerde eine solche Moeglichkeit sehe begrueßen". Mies van der Rohe, April 7, 1961. In Mies muss in Berlin bauen! (Mies must build in Berlin!). Bauwelt, v. 17/18, 1st May 1961, p. 519.

28

Ulrich Conrad was one of the most important german architecture and urban planning critics and publicists of the second half of the 20th century.

29

"Dass Mies van der Rohe wieder in Berlin baue, ist unser Wunsch für ihn und uns an seinem 75. Geburtstag". Bauwelt 1961, v. 13, p. 365-380.

30

SCHULZE, Franz. Mies van der Rohe. Leben und Werk. Berlin, Ernst & Sohn, 1986, p. 311.

31

On the possibilities of artistic exploration of the "universal space" of the Grand Exhibition Hall of the Neue Nationalgalerie see: WOELK, Imke. Der offene Raum. Der Gebrauchswert der Halle der Neuen Nationalgalerie in Berlin von Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. PhD Thesis. Berlin, Fakultät VI Planen Bauen Umwelt der Technischen Universität Berlin, 2010 <https://bit.ly/3vmgl8s>.

32

Statement by Mies in the film Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, directed by his daughter, Georgia van der Rohe. Knoll International/ZDF, Mainz, 1979.

33

Pseudonym of the Belgian sculptor Henri Van Herwegen (1940-2019).

34

"In der Neuen Nationalgalerie, dem letzen Bau meines Vaters, war gerade ein flugkörper von Panamarenko aufgebaut. Ein Glücksfall. Er füllte den riesigen Ausstellungsraum und schien nachts, hell beleuchtet, märchenhaft durch die Glassfassaden". VAN DER ROHE, Georgia. La donna è mobile. Mein bedingunsloses Leben. Berlin, Aufbau-Verlag, 2005, p. 289.

35

RILEY, Terence, BERGDOLL, Barry (ed.). Mies in Berlin. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Die Berliner Jahre 1907-1938. München, Prestel, 2001.

36

SCHULZE, Franz. Op. cit., p. 315.

37

MERTINS, Detlef. Op. cit., p. 389-390.

38

Originally designed in steel by Mies, the main building material had to be adapted to concrete due to the strong salty sea air. Mies noticed how badly the iron railing of the hotel balcony in Havana was affected by rust. SCHULZE, Franz. Op. cit., 1986.

39

SPAETH, David. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: Ein biographischer Abriß. Mies van der Rohe. Vorbild und Vermächtnis. Frankfurt a. Main, Deutsches Architekturmuseum, 1986.

40

FRAMPTON, Kenneth. Tradition und Moderne im Werk von Mies van der Rohe.1920-1968. In Mies van der Rohe. Vorbild und Vermächtnis. Deutsches Architekturmuseum, Frankfurt a. Main, 1986.

41

FRAMPTON, Kenneth. Op. cit., 1986, p. 52.

42

“Wie Sie sehen, habe ich die Idee des Vorhangs nicht aufgegeben. Ein sorgfaeltig ausgewaehlter Vorhang wuerde nicht nur das Sonnenschutzproblem loesen, sondern auch die architektonische Erscheinung der grossen Halle angenehm bereichern. Was auch immer wir an dieser Stelle als Sonnenschutz vorsehen werden, er darf auf keinen Fall die bauliche Klarheit beeintraechtigen und muss immer eine unabhaengiges Additiobn zum Bau sein“. In Schreiben Ludwig Mies van der Rohes an den Generaldirektor der Staatlichen Museen Stephan Waetzoldt, v. 28. Februar 1966.

43

REICHERT, Martin. Der Unsichtbare Architekt — die Grundinstandsetzung der Neuen Nationalgalerie als Zielkonflikt-Moderation. In BRANDT, Sigrid und HASPEL, Jörg (ed.). Icomos-Hefte des Deutschen Nationalkomitees, LXIII. Denkmal – Bau – Kultur, Konservatoren und Architekten im Dialog. Kolloquium anlässlich des 50jährigen Jubiläums von Icomos Deutschland. Berlin, 2017, p. 58.

44

"Es hat ja geheissen, jeder sollte nur fuenf Minuten sprechen. Wat da geschwindelt wurde! Ich will hier nur den Stahlfritzen danken, und den Betonleuten. Und als das grosse Dach sich lautlos hob, da hab'ich gestaunt!". SCHULZE, Franz. Mies van der Rohe. A critical biography. Chicago/London, University of Chicago Press, 2012, p. 310-311.

45

VAN DER ROHE, Georgia. "Ab neun Uhr früh Chicagoer Zeit erwartete mein Vater einen telefonischen Bericht über die Eröffnung. So ging ich um vier Uhr nachmittags ins Hotel und rief ihn an. Natürlich war er vor lauter Aufregung und Anspannung schon früh aufgestanden. Er freute sich über die größe Zustimmung der Berliner, die vor allem ihm, dem Architekten, galt. Der Berliner Witz kommentierte den Bau: Da steht der Tempel, als wenn er schon immer da gestanden hätte". In VAN DER ROHE, Georgia. Op. cit., p. 249.

46

"Er war der am stärksten abstrahierende Architekt des Jahrhunderts". SCHULZE, Franz. Op. cit., p. 332.

47

CHIPPERFIELD, David. A speech on the restoration project for the Neue Nationalgalerie delivered at the "Form versus function. Mies und das Museum". David Chipperfield Architects <https://bit.ly/3JVlEzO>. Emphasis added.

48

BRANDI, Cesare. Op. cit..

49

CARBONARA, Giovanni. Tendencias actuales de la Restauración en Italia. Loggia, Arquitectura & Restauración, v. 6, 1998, p. 12-23 <https://bit.ly/35dry0n>.

50

"L'opera d'arte nasce nella coscienza dell'artista [...]; l'opera è realtà pura, incorruttibile, non così il materiale che, degradandosi naturalmente o per le molteplici vicende istoriche [...]". In CARBONARA, Giovanni. Avvicinamento al restauro: teoria, storia, monumenti.(Capitulo secondo) Fondamenti di uma visione critica e creativa del restauro. Napoli, 1997, p. 405.

51

"Still, there will be (and certainly have been), people who would insert restoration into precisely this most intimate and unrepeatable phase of the artistic process. This is the most serious heresy of restoration”. BRANDI, Cesare. Op. cit., 2005, p.63-64.

52

AG-Bau Beschlussvorlage zur Gesamtsanierung der Neuen Nationalgalerie, Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung (BBR) 4.3.2011. Apud REICHERT, Martin. Op. cit., 2017, p. 52.

53

"Der paritätische Abstimmungsprozess erfolgte unter unserer Moderation zwischen den Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin als Nutzer, der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz als Bauherr, dem Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung (BBR) als baufachlicher Vertretung des Bauherrn, dem Lan-desdenkmalamt Berlin, dem Landesdenkmalrat und den be-teiligten Fachplanern und wurde von dem ehemaligen Pro-jektleiter Dirk Lohan (Enkel Mies van der Rohes) und dem Mies-Experten Prof. Dr. Fritz Neumeyer beratend begleitet". In REICHERT, Martin. Op.cit., 2017, p. 54.

54

Im Zentrum unserer Planung stand deshalb die Zielkonfliktmoderation zwischen den Bedürfnissen der Nutzung und jenen des physischen Baudenkmals". Idem, ibidem, p. 52.

55

SALVO, Simona. Il restauro del grattacielo Pirelli: la risposta italiana a una questione Internazionale. In Arkos: Scienza e Restauro dell'Architettura, n. 10, Firenze, 2005, p.64-71. SALVO, Simona. Arranha-céu Pirelli: crônica de uma restauração. Desígnio, n. 6, São Paulo, 2006, p. 69-86.

56

“Adolphe Napoléon Didron (1806-1867): "Regarding ancient monuments, it is better to consolidate than to repair, better to repair than to restore, better to restore than to rebuild, better to rebuild than to embellish; in no case must anything be added and, above all, nothing should be removed". JOKILEHTO, Jukka. A History of Architectural Conservation, Oxford, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1999, p. 138.

57

Idem, ibidem, p. 155. Emphasis added.

58

"Eingriffe und Veränderungen sollten sich dabei immer auf das minimal erforderliche Maß beschränken". REICHERT, Martin. Op. cit., p. 54.

59

CHIPPERFIELD, David. Op. cit.

60

BRANDI, Cesare. Op. cit., p. 55-59. The potential oneness of a work of art.

61

Idem, ibidem, p. 73.

62

CHIPPERFIELD, David. Op. cit.

63

"Wir konnten das AG Bau-Gremium durch zwei Argumente überzeugen: Erstens sind die unterirdischen Erweiterungen weder von außen noch von den öffentlichen Bereichen im Inneren wahrnehmbar; zweitens stellen die Autonomie und die Existenz aller Funktionsbereiche eines Museums einen eigenen Denkmalwert dar, der nicht durch die Auslagerung von Depots relativiert werden sollte". REICHERT, Martin. Op. cit., p. 55.

64

"Wir stiegen mit der These ein, dass die beiden Depots erkennbar umgenutzt, nicht aber neu gestaltet werden würden". REICHERT, Martin. Op. cit., p. 60.

65

BRANDI, Cesare. Op. cit., p. 93. Emphasis added.

66

The technical and functional aspects of the restoration of the Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin are addressed by research colleague Klaus Brendle in his article "Modern" Building Techniques and Historical Monuments. Conservation, repair, reintegration, restoration, reconstruction and new-construction parts for the preservation of Mies van der Rohe's New National Gallery of 2021 in Berlin.

67

REICHERT, Martin. Monument preservation and renewal concept. In Arne Maibohm (ed.). Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin: Refurbishment of an Architectural Icon. Berlin, JOVIS Verlag GmbH, 2021, p. 121. Emphasis added.

68

“Dunque, si restaura in architettura facendo architettura cosi pure in scultura e pintura.[…] Architettura e progettazione di restauro o, meglio, 'al servizio del restauro' dei beni culturali, vale a dire un modo di progettare fortemente guidato da una solida coscienza e attenzione storica”. In CARBONARA, Giovanni. Il restauro fra conservazione e modificazione. Principi e problemi attuali. Napoli, Artstudiopaparo, 2017, p. 15.

about the author

Betânia Brendle is associate professor emeritus at the Federal University of Sergipe, Brazil, with a post-doctorate at the Technische Universität Dresden (Institut für Baugeschichte, Architekturtheorie und Denkmalpflege, 2015). PhD in Urban Design from Oxford Brookes University (1994), Specialization in Architectural Conservation by ICCROM Rome (1987) and Restoration of Historic Monuments and Revitalization of Historic Centres by PNUD-Unesco Peru (1980) and a degree in Architecture and Urbanism by the Federal University of Pernambuco, Brazil (1976). She is a member of The International Council of Monuments and Sites — Icomos/Brazil.

![The curtains of the Neue Nationalgalerie, designed by Mies as an inseparable part of the building. On the background, Scharoun's Philarmonie and St Matthäis-Church<br />Foto/photo Günther Metzner, 1968 [Landesarchiv Berlin]](https://vitruvius.com.br/media/images/magazines/grid_9/af8814cce95f_brendle_nationalgalerie02.png)

![The curtains of the Neue Nationalgalerie, designed by Mies as an inseparable part of the building. On the background, Scharoun's Philarmonie and St Matthäis-Church<br />Foto/photo Günther Metzner, 1968 [Landesarchiv Berlin]](https://vitruvius.com.br/media/images/magazines/gallery_thumb/af8814cce95f_brendle_nationalgalerie02.png)